Summary

- Guyana’s Natural Resource Fund institutional and Governance framework are in line with the IMF’s recommendation and the models adopted by some of the largest SWFs across the globe.

- The withdrawal rule of the fund is economically justified against the development needs of the country.

Background

Following the successful passage of the amended Natural Resource Fund Bill, 2021 which is now the Natural Resource Fund (NRF) Act, commentators, analysts and foreign experts alike are still debating some crucial elements of the NRF Act. Particularly, the governance structure and the withdrawal rules. This article seeks to conduct somewhat of a literature review to illustrate empirically the institutional arrangements and governance structure of some of the largest SWFs in the world. The aim is to also allow readers to draw comparison to the current legal, institutional and governance set up of Guyana’s NRF and the withdrawal rules.

Discussion and Analysis

Why do countries establish Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs)?

Generally, countries establish SWFs for four primary reasons. Firstly, SWFs act as intergenerational transfer mechanisms, where future government pensions, asset liquidity and fiscal revenues are guaranteed by today’s export earnings such that, future generations can continue to live prosperously when the countries natural resources are exhausted – using the earnings of their forefathers. Secondly, most SWFs of all country types are created to diversify a country’s income so that it can respond to shocks to the country’s comparative advantages. In the event of a competitiveness crisis faced by a country, it can utilize its SWF assets to reinvest in new sectors of the economy that can revive the country’s competitive advantages.

Thirdly, SWFs are established to increase the return on assets held in their central bank reserves. They can raise returns above the 3-5 % annual returns garnered by most foreign exchange reserve holdings, by investing in securities other than U.S or European sovereign bonds.

In recent times, this desire has become prevalent with the rapid expansion of foreign exchange stocks in many emerging markets and the decline of the U.S dollar – and thus lower returns on dollar-denominated debt (Balin, 2008).

And finally, the fourth is that – some SWFs, seek to promote investment from multinational corporations and technological transfer to domestic industries. In so doing, a fund would have to acquire a majority stake in a company or form a coalition with shareholders. Henceforth, with its voting power, the SWF can appoint corporate board members who could direct a company to invest in the SWF’s home country and especially, establish research and development facilities there (Balin, 2008).

The Institutional and Governance Structure

Regarding the objectives and governance structures of SWFs, it must be recognized that the policy objectives of SWFs vary, depending on the broad macro-fiscal objectives that they aim to address. As such, the organizational structure needs to have a clear separation of responsibilities and authority. Thus, a well-defined structure builds a decision-making hierarchy that limits risks viz-à-viz ensuring the integrity of and effective control over SWF management activities (IMF Working Paper, 2013).

The institutional frameworks of SWFs differ from one country to another. Irrespective of the governance framework, to minimize potential political influence that could hinder the achievement of its policy objectives, the operational management should be conducted on an independent basis. The “manager model” and the “investment company model” are the two dominant forms of institutional setup.

Citing IMF Working Papers (2008 & 2013), the legal owner of the pool of assets constituting the SWF (usually the Ministry of Finance) gives an investment mandate to an asset manager – that is, in the manager model. Within this model, there are three main subcategories:

- The central bank manages the assets under a mandate given by the ministry of finance (e.g., Botswana, Chile and Norway). In this case, the central bank may choose to use one or more external (private) funds for parts of the

- A separate fund management entity, owned by the government, is set up to manage assets under a mandate given by the ministry of finance, such as the Government Investment Corporation (GIC) of In this case, the manager may also have other asset management mandates from the public sector. For example, the GIC manages parts of the reserves of the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

- The ministry of finance gives mandates directly to one or more external (private) fund This model is generally not recommended, since awarding contracts to external fund managers is in itself an investment decision that should be carried out at arm’s length from a political body, and the evaluation, monitoring, and termination of management contracts requires specialized skills more likely to be found in a dedicated investment organization. However, for countries with severe human capital constraints, it can be the only feasible solution.

In the second model, that is, the investment company model, the government establishes an investment company that in turn owns the assets of the fund. This model is usually employed when the investment strategy implies more concentrated investments and active ownership in individual companies (Temasek, Singapore), or the fund has a development objective in addition to a financial return objective.

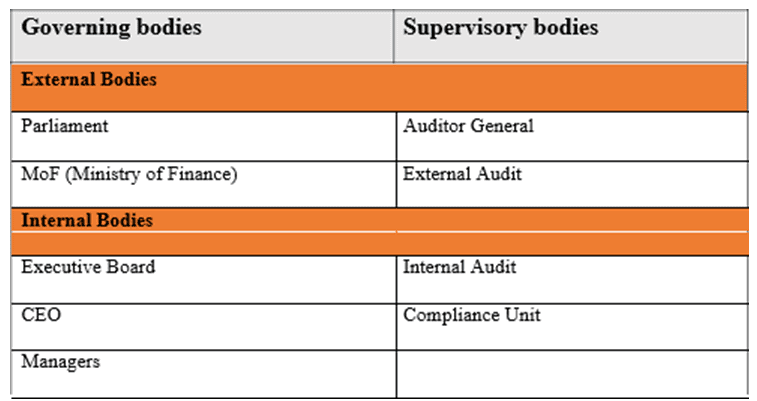

In the organizational structure of SWFs, it is important to distinguish between governing and supervisory bodies. The governing bodies constitute a system of asset management responsibilities. The authority to invest is delegated from the top entity of the governance system, through the various governing bodies, down to the individual managers of assets. The delegation implies a gradual increase in the granularity of regulations about responsibilities as we move down the ladder of the organizational system. The role of the supervisory body is to verify the supervised unit in acting under the regulations set by the governing body immediately above it in the governance structure.

It is also helpful to distinguish between those bodies that are internal and external to the organization. The table below illustrates the SWF government structure:

Notwithstanding the divergence in the governance models of SWFs inter alia, due to differences in political institutions, some common principles should be considered essential to any well-governed SWF. To this end, it must be recognized that the principal aim in the establishment of a governance structure for the SWF is that the bodies established to manage the assets of the SWF are essentially trustees on behalf of the people of the country. Therefore, one of the fundamental concerns is to establish a structure that will underpin the legitimacy of the SWF’s operations and ensure that the decisions taken in the management of the SWF reflect the best interest of the owners of its assets.

The legal framework

The effective management of SWFs is underpinned by a robust legal framework for ensuring a sound institutional and governance arrangement. The legal framework should among other things:

(1) provide clearly for the legal form and structure of the SWF and its relationship with other state agencies; (2) be consistent with the broader legal framework governing government’s budgetary processes; (3) ensure legal soundness of the SWF and its transactions; (4) support its effective operation and the achievement of its stated policy objective (s), which should be economic and financial in nature and; (5) promote effective governance, accountability and transparency.

It should be noted that there are a wide variety of legal frameworks, however, generally, SWFs are established (1) as separate legal entities under law with legal identities and full capacity to act; (2) take the form of state-owned corporations also with distinct legal persona; or (3) as a pool of assets owned by

the state or Central Bank, without a separate legal entity. While all of these forms are compatible with recognized practices and principles, the legal basis for the SWF must establish which form the SWF has.

There is also a wide variety when it comes to the degree of granularity of primary legislation. This will partly reflect different traditions and/or constitutional requirements across countries. Some countries have very short primary legislation but more granular secondary legislation. There are also differences in how much delegation of authority laws in different countries provide for. Again, many levels of granularity may be compatible with recognized international practices. But it is essential that the overall legal framework provides for real delegation from owner to manager and that it grants the operational manager independence within the guidelines set by the owner (IMF Working Paper, 2013, Pg.9).

In practice, different legal forms may have implications for both the tax position and immunity of investments. Investments through Central Banks are normally protected by sovereign immunity and may also enjoy tax privileges in recipient countries. Taxation of investments through corporate structures may depend on the extent to which these investments are viewed as an integrated part of the government’s financial management. Taxation treatment of SWF investment can also depend on provisions in bilateral tax agreements (for example, Norway has negotiated tax exemptions for its SWF investments in several bilateral tax treaties).

Funding and Withdrawal Rules

Funding and withdrawal rules are specific to the type of SWF and set out in legislation. Withdrawal rules for these funds take into account future estimated obligations. Except under exceptional conditions, funds cannot be withdrawn and require, for instance, targeted levels of the fund to be exceeded as well as Parliamentary approval. Funding and withdrawal rules for other SWFs are usually tied to the source of funds. For example, fiscal stabilization funds are typically funded from revenue contingent deposit rules (i.e., exceeding a target), and withdrawal rules are typically crafted to meet budget deficits. Reserve investment corporations are typically funded with reserve adequacy requirements, and some funds have established asset trust contracts with sponsors that change periodically. Other differences in the rules exist: some funds keep capital and returns while others pay our targeted annual dividends to the owner; some can invest directly in specific local investment projects, though respondents note that such transactions are reflected in the budget and are compliant with local and international government statistical rules (where indicated).

Basic Principles of Risk Management – adopted from IMF Working Papers (2008 & 2013)

Fiduciary Responsibility: The investment manager needs to be conscious at all times of its fiduciary responsibility to the fund’s owner in safeguarding the fund’s interests and reputation.

Risk Tolerance: The investment manager needs to have a clear understanding of the fund owner’s risk tolerance and act accordingly in discharging its investment responsibilities.

Risk-Conscious Culture: The Investment manager needs to promote a risk conscience culture within the organization with senior management setting the tone.

Risk Ownership: The ownership of risk should be established within the investment management entity and between the fund’s manager and owner.

Risk Governance: There needs to be a well-defined governance structure for risk management within the investment management entity for the fund.

Risk Identification and Assessment: All material risks for the fund must be identified, assessed and accepted through structured and systematic processes before investment.

Diversification of Risks: Risks should be diversified systematically to limit concentration of exposures, and reduce over-reliance on individual systems, processes, providers and people.

Checks and Balances: Investment and operational processes should have in-built checks and balances, with clear segregation of responsibilities, to minimize errors, avoid conflict of interest and reduce the possibility for collusion.

Risk Measurement: All material risks for the fund should be measured, either quantitatively or qualitatively, without overreliance on any single metric, and monitored with appropriate frequency.

Overview of SWFs in Asia

SWF assets of Asian countries currently account for about 40 per cent of total global SWF assets. The growth of Asian SWFs is a relatively new phenomenon which emerged as a consequence of two economic factors. Firstly, as the large export-driven East Asian countries accumulated enormous foreign currency reserves, policymakers started evaluating the desirable level of reserves. The second factor was that the U.S dollar (the main reserves currency), depreciated significantly in recent years and the returns of these reserves’ investments came under scrutiny. Thus, it was decided to establish SWFs as a tool to address these issues (World Bank, 2014).

On the contrary, other large SWFs in East Asia such as Singapore and Malaysia were originally established to enhance the efficiency of managing government’s holdings in domestic corporations, which were accumulated in the process of government-led economic development. These funds then started to invest internationally, and today; these funds operate more like a commercial investment company. Additionally, a few countries namely Brunei and Timor-Leste had established their SWFs with commodity revenues as savings or stabilization funds. These types of funds have relatively fewer needs for short-term income streams. Rather, they need high long-term returns with prudent levels of risk to support productive investment in growth-enhancing and poverty-reducing spending on needed infrastructure, such as agriculture, health, education and basic service delivery. In history, however, it was evidenced that in some instances, these funds have amplified rather than mitigated the adverse effects of oil and gas windfalls (World Bank, 2014).

China’s SWF

China’s SWF, the China Investment Corporation (CIC), was established in September 2007 – and is one of the largest SWFs in the world. The CIC was created to improve the rate of return on China’s $1.5 trillion in foreign exchange reserves and to absorb some of the country’s excess financial liquidity. The CIC is a semi-independent, quasi-governmental investment firm, mandated to invest a portion of China’s foreign exchange reserves. The CIC reports directly to China’s State Council, conferring it with the equivalent standing of a ministry, and the State Council’s leader.

Several international finance experts had expressed some concerns about the recent growth in SWFs and the CIC in particular. Some analysts had argued that major shifts in SWF investments could potentially disrupt global financial markets and the U.S economy. On the other hand, other analysts were less concerned about SWF and the CIC and welcomed their participation in international investment markets (CRS Report for Congress, 2008).

Nonetheless, China responded by maintaining that the CIC will prove to be a source of market stability. But despite its reassurances in this regard, there were calls for greater oversight and regulation of SWFs. Some experts suggested elements to be included in such guidelines such as standards for transparency, governance and reciprocity. It was also suggested that the United States review its laws and regulations governing foreign investments in the United States, with the possibility of implementing special procedures or restrictions on proposed investments by SWFs – inclusive of limits of SWF ownership of

U.S companies, financial reporting requirement, and restrictions on types of equity investments SWFs can make in U.S firms (CRS Report for Congress, 2008).

Kuwait Investment Authority

The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) is mandated to achieve long-term returns on Kuwait’s surplus oil revenue and to provide an alternative source of government income for when the country’s oil resources are depleted. The KIA is set up as an autonomous government institution and is responsible for the management and administration of the Future Generations Fund (FGF) and the General Reserve Fund (GRF), as well as any other fund entrusted to it by the Kuwait Minister of Finance (Behrendt, 2008).

The SWFs of Abu Dhabi

The Emirate of Abu Dhabi controls three relevant SWFs: the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), Mubadala Development Company and the International Petroleum Investment Company (IPIC). All three of these funds, over several decades, were established to manage the emirate’s oil and gas income, strengthen its position in the regional and global oil markets and eventually help diversify Abu Dhabi’s economy away from risks posed by volatile oil markets (Behrendt, 2008).

Dubai SWF

While Abu Dhabi and Kuwait have managed their foreign investments through SWFs for decades, Dubai’s portfolio of SWFs was only developed just over a decade or so, to benefit from global investment opportunities. As such, Dubai does not have an extensive track record of managing the government’s external assets. Dubai’s investment landscape was fairly fragmented, and private ownership appeared to be much more dominant there than other countries (Behrendt, 2008).

Andrew Ang (2010) (a study by the Columbia Business School) proposed four benchmarks of SWFs to the extent where the benchmarks should take into account the economic and political context underpinning the establishment of the SWF, and the role that the SWF will pay as one part of government overall policy. The first benchmark is legitimacy – which should ensure that the capital of the SWF is not immediately spent and instead, is gradually disbursed across the present and future generations. The second benchmark is that it should recognize the implicit liabilities of the SWF by taking into account its role in government fiscal and other macro policies. The third is setting the performance benchmark which should complement the governance structure of the SWF. And fourthly, the long-term horizon requires an SWF to consider the long-run equilibrium benchmark of the markets in which the SWF invests and the long-term externalities affecting the SWF.

SWF and a developing country perspective

Developing countries have accumulated large foreign exchange assets in SWFs during the 2000s which is of growing importance. It is however recognized that despite the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves by developing countries is partly a consequence of deep financial integration and the instability that it can generate, such actions feed into global imbalances through “fallacy of composition” effects (a

simple definition for this term is where an individual assumes that something is true of the whole just because it is true of some part of the whole. For example, the paradox of savings: it is believed that if one individual can save more money by spending less, then the entire economy can save more by spending less. However, this is far from reality, because if everyone reduces spending then demand for goods and services will fall which will, in turn, lead to lower growth and revenue for businesses.

As a consequence, businesses may lower wage and lay off individuals, and people will have less income to spend and less to save). Griffith-Jones & Ocampo (2008) argued that though these strategies may be rational for developing countries, they contribute to global imbalances. Simultaneously, SWFs have played somewhat of an unexpected stabilizing role by providing the funds that have helped to stabilize the banking system of developed countries during periods of financial turbulence. They have also generated an important opportunity to increase financial cooperation among developing countries, both on a regional basis and a broader scale.

Moreover, it is worthwhile to note that SWFs are considered to be an important source of capital in the global financial markets. And, these funds originate from countries with rich natural resources with favourable international balance of trade in ono-commodity goods and services (Patton, 2012). To lend a more meaningful insight with regards to the impact of SWFs on economic development within the context of a developing economy, in this respect, the discussions presented hereunder – examines some empirical evidences in the case of Nigeria and Uganda.

Oleka et., al (2014) conducted an empirical analysis on SWF and economic growth in Nigeria which was published in Journals of Economics and Finance (www.iosrjournals.org) – the study found that the link between SWF and economic growth in Nigeria is statistically significant but not positive. The reason for this outcome is because SWF is relatively new in Nigeria, together with several challenges facing its operations and as such, has not contributed much to the growth rate in GDP of the Nigerian economy. Additionally, the study found that the SWF gained significant recognition in the global economy and has been acknowledged as a catalyst and veritable channel for economic growth especially in developed economies but the contribution has been less than satisfactory in Nigeria.

Guyana’s economy is largely underdeveloped henceforth, is savings necessary at the onset of oil production?

Having thus outlined the governance frameworks, legal models and macroeconomic perspectives among other key elements – the author sought to contextualize the notion of whether savings of Guyana’s oil revenues is necessary at the onset of commercial oil production in 2020 while the country has a massive infrastructure deficit that needs developing.

In a developing economy, the merit of maximizing current spending from resource revenues is that it provides an opportunity to increase the consumption of a poor population. It also relaxes potential borrowing constraints and thereby enables increasing investment in domestic capital with high rates of return. Therefore, constraining spending inter alia SWF with restrictive spending rule may involve welfare loss; such a situation existed in Uganda (Hassler et.al, 2015).

To further put this into perspective, this author is of the view that some commentators along with other sections of the media are taking things a little bit overboard for the badly negotiated Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) between the multinational oil company operating in Guyana and the Government of Guyana. Though one would agree that the contract could have been better, after all, it is not an entirely bad deal and therefore, it would be in the spirit of national interest that we collectively move on and now

shift focus on other critical aspects. To this end, particular reference is made on how we are going to spend the oil revenue to develop this country and by doing so, this also addresses the question raised herein on whether an SWF is necessary.

Essentially, a Sovereign Wealth Fund is a savings fund for a country that has large surplus funds and it is then being used to invest in various financial instruments in the global capital markets. In other words, if Guyana earns $100 billion in oil revenues and it is then locked away for investment in an SWF in which those investments are going to earn say 5 or 10 % return on investment – would this model be of any direct economic benefit to the people of Guyana? The answer is no, unfortunately.

Another point of interest is that countries that have created SWFs, they were not at all as underdeveloped as Guyana is currently. For example, Norway’s oil industry is about four decades old and they had created their SWF (Government Pension Fund – Global) in 1990, that is about twenty-eight years ago which means Norway’s SWF was created just over the first decade when their Petroleum industry started to develop. More interestingly to note – even before Norway’s oil era – it was very much an advanced country before oil came. In fact, according to a report published by PETRA (a Norwegian Government foundation established in 1989, to transfer knowledge and experience on petroleum resource management and technology), it was stated that before Norway’s oil era – they had a sound economy; well-developed welfare; high employment; stable and homogenous population; moderate-high technology; efficient government; political consensus; extensive trade; friendly nation; pietism and caring for nature; and politicians trusted. Another good example is China: China has the second-largest SWF in terms of asset size of US$900 billion, after Norway, and their SWF was only created in 2007. Bearing in mind that China is one of the leading emerging economies on the global stage and has enormous amounts of surplus funds to the extent where China virtually funds trillions of dollars in the U.S government’s spending and other parts of the world as is universally known.

Guyana on the other hand, the consolidated fund is almost always in deficit and so is the national budget which is almost always a deficit budget which means the country borrows heavily to fund budget spending. This is coupled with the fact that Guyana is a developing nation and therefore needs massive investments in infrastructure, health care, education, information and communication technology etc.

In the final analysis, Guyana does not need to save all of the oil revenues at the onset of oil production, instead, a greater portion of the oil revenues should be utilized to advance massive infrastructural developments among other crucial aspects of national development, which the country badly needs.

Conclusion

In view of the foregoing, one can observe that the current institutional and governance framework of Guyana’s NRF Act is in line with some of the recommended models which other major SWFs adopted across the globe. Notably, the NRF model Guyana has adopted is in line with the International Monetary Fund’s recommendation.

With respect to the withdrawal rules, the justification rests on the massive development needs of Guyana. It is important to highlight as well that given the historic nature of Guyana’s political economy, the country’s development has been largely stymied. For example, the new bridge across the Demerara river should have been built more ten years ago, the same can be said for the Amaila falls project, a modern state of the art hospital, etc. Hence, it is against this background that the government of the day is on the right path to draw down the resources from the fund in order to accelerate the rate of development at a rapid pace.

About the Author

Joel Bhagwandin is a Financial Analyst and has been providing insights and in-depth analyses on national cross cutting issues surrounding public policy, economic and finance issues for the past 5+ years on a variety of thematic areas within this sphere. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author, and not necessarily to the author’s employer, organization, committee, or other group or individual. The author is the holder of a master’s degree in banking & finance and he is [currently] undertaking four professional certifications in Corporate Finance through the Corporate Finance Institute (i.e., the FMVA, CBCA, CMSA & BIDA professional designations).