Algeria has recently introduced a new hydrocarbons law bill whose goal is to increase the attractiveness of its petroleum fiscal framework after years of reduced foreign investment in the oil and gas sector. However, like Guyana, success in establishing new frameworks for oil and gas development depends on political resolution.

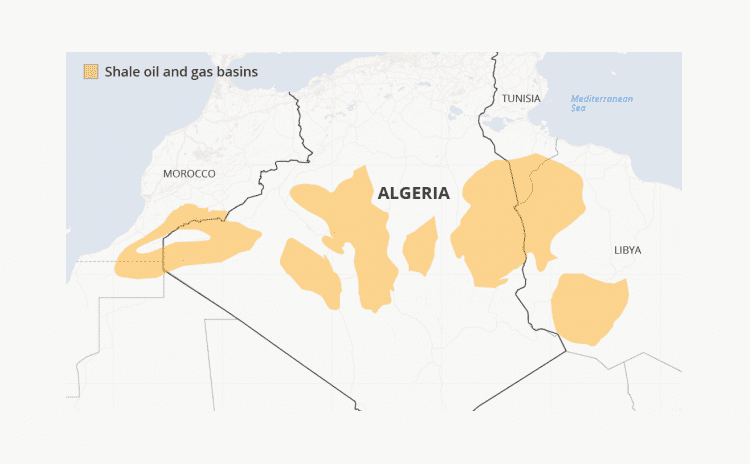

GlobalData, a leading data and analytics company, says Algeria needs to boost its hydrocarbons production on a long-term basis to support its economy, which has been hit hard since the reduction in oil prices in 2014. This year, the country will produce 1.15 million barrels per day of oil (declining trend) and 9.46 billion cubic feet of gas per day (some new projects may increase gas production between 2019 and 2022, but then the trend will be declining). Algeria is still overly dependent on hydrocarbons, which represent 40% of government revenues and 95.6% of exports.

The new bill reintroduces production sharing agreements (PSAs) and reduces the complexity of the previous petroleum framework by simplifying the structure of the fiscal terms. Prospective licensees can now sign a royalty/tax (R/T) participation contract, a PSA, or a risk service agreements (RSA).

Alessandro Bacci, Oil and Gas Analyst at GlobalData, comments: “The new R/T participation contract, in which licensees will continue to be restrained to up a 49% participation stake and to pay surface tax, royalty, hydrocarbons revenue tax, and additional income tax, shows a significantly higher Internal Rate of Return (IRR) in comparison with the previous regimes’ IRRs.”

Bacci adds: “The framework for PSAs and RSAs is, in practice, very similar to the pre-2005 PSA/RSA framework. Licensees’ shareholding in a contract is not limited, with only their share of production (PSA) or revenue (RSA) limited to 49% ─ while Sonatrach pays all the taxes on behalf of the licensees. However, the attractiveness of both the new PSAs and RSAs will depend on the specific terms of each future signed contract.”

The new bill is a step in the right direction but improving the petroleum fiscal framework may not suffice as there are other hurdles at the administrative, political, and technical levels, which may prevent licensees from investing in Algeria’s upstream sector.

Bacci concludes: “At the political level, after the departure of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April 2019, political unrest remains, and the draft hydrocarbons law immediately drew significant protests. It is unclear whether the presidential elections, initially planned for July and now scheduled for December 2019, will get Algeria out of the impasse.”

Guyana currently uses a model PSA framework and has signed several such contracts with oil companies operating off of its coast. The PSA between Guyana and US oil major ExxonMobil, the first company to discover oil in the country, provides for 2 percent royalty and 50 percent profit oil.

As the South American country prepares for oil production, now just months away, political uncertainty surrounding the holding of elections, now set for March 2020, has impacted the establishment and implementation of a number of measures for the new petroleum industry. Nevertheless, Guyana is now on course to become one of the major producers in the region.