By Dr. Arlington Chesney – OilNOW

The Caribbean, indeed, the world, is prioritising the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the modernisation of their national economies. This is associated with the proliferation of devices, such as, IoT, IIoT and InstructGPT with its sibling, ChatGPT, and Microsoft’s AI for Earth Programme.

The agricultural sector is part of this transformational process with the use of AI in agriculture globally projected to increase from US$1.1 billion in 2019 to US$3.8 billion by 2024. This favourable projection is linked to AI use in agriculture being associated inter alia with increased efficiency and effectiveness, resulting in increased profitability and industry sustainability.

These beneficial outcomes are primarily due to the plethora of associated devices that are grouped as (1) algorithmic and (2) autonomous.

The algorithmic devices can collect, analyse and interpret gigantic quantities of data and make projections and/or predictions that exceed human capacity and reliability, improving with increasing data range and use.

This has led to AI being used inter alia to:

- In crops, (i) forecast weather and hence, best timing of planting; (ii) determine fertiliser, pesticide and irrigation water use; (iii) optimise supply chains; and (iv) forecast market peculiarities and readiness.

- In livestock, (i) determine feeding patterns; and (ii) management of endemic diseases.

There are many autonomous devices, including drones and robots, conducting precision operations, such as:

- In crops, land management and agronomic practices, including pest control, and pollination,.

- In livestock, milking, feeding and general husbandry.

- In farm administration and management, transport, haulage and sanitation.

What are the implications for the agriculture and food sectors in an oil rich Guyana and, by extension, CARICOM? Guyana’s President, Dr. Mohamed Irfaan Ali, CARICOM’s Lead Head for Agriculture, recently stated that the “Caribbean market must be positioned as a high-value specialised one”. It is now well demonstrated that the World Trade Organisation’s requirement for globally produced commodities to have relatively free access to national markets of developing countries, such as, Guyana, has hindered the growth of indigenous agricultural and food sectors. Nonetheless, because of potential geopolitical pressures and the established trading patterns for food commodities prevailing in Guyana and CARICOM, this status quo will not change significantly soon. Therefore, achievement of the position identified by President Ali, that is, food supply to a “high-value specialised” market, must be generally done with global competitiveness.

With the abundance of stated benefits associated with the use of AI in agriculture, the potential use in achieving competitiveness required of Guyana’s agriculture and food sector needs to be examined.

The use of AI in agriculture would not pose a mental block to practitioners in Guyana’s agricultural sector who have historically introduced innovative practices and techniques. For example, the sugar industry has utilised aircraft for fertilising and pest control and drones for assessing the state of its available lands. Similarly, the rice industry has “adapted” caged wheels for tractors operating under waterlogged conditions, utilised aircraft for seeding and fertilising and a land leveling “machine” which could be considered as a precursor within the concept of Machine Learning Systems.

Further, at a basic algorithmic level, farmers have established their timings for land preparation, planting and, hence, harvesting with traditional knowledge of the climatic seasons. Within that broad canvas, they determine best times to plant their short term and tree crops with the advent of the “full moon”. More recently, they have become aware that long droughts, associated with climatic changes, are followed by severe pest infestations. Consequently, they make early preparations to effect control.

Agriculture is a complex social, economic and environmental system that responds to the particular and peculiar metrics of Guyana; these metrics are/will be robustly dynamic with the impact of climate change. Consequently, the uses of AI in agriculture in Guyana can’t be transferred wholesale from the countries in which they are being used successfully. They must be tested, adapted and customised to ensure fit for purpose in Guyana. This process, which is tantamount to being a “living laboratory”, requires enhanced—numbers and specialties—technical and financial capacities. With respect to finance, Guyana can use some of its substantial current and projected oil and gas revenues. Once used wisely, this will be a profitable investment in the development of the country’s sustainable agricultural and food sectors of the future.

At the algorithmic level, particularly as it relates to data on weather patterns, the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology, in association with national Hydrometeorological Services, like Guyana’s, is making available Numerical Weather Predictions to the public, including those in the agricultural and food sectors. With support from the Extension Services, this information could then be used by individual small and large agri-entrepreneurs to plan, with a level of precision, for farm activities. These would include time of land preparation, planting, weed control, husbandry practices and harvesting. This is particularly critical for the agriculturally important, but difficult to manage, heavy clay/silt soils of Guyana’s coastal and riverine areas.

Small farmers currently dominate the country’s food production sector. With their limited technical and instrumental capacity, the template of institutions (ministries or parastatals or agriculturally based associations) collecting and analysing data and developing projections must be promoted and strengthened. As stated previously, the use of AI, at both the algorithmic and autonomous levels, will require “living laboratories”. It’s recommended that these be located at the various ecological zones within Guyana. This will enhance possibilities of minimising risk whilst optimising possibilities for sustainable enterprise development. This is made more necessary because of the current high costs of autonomous devices.

A strong, innovative, visionary and responsive institutional model is essential.

Notwithstanding the above, there are some potential uses for AI in the developing agriculture and food sectors in Guyana. Firstly, at the algorithmic level, weather and soil data could be collected and analysed to project with significant statistical accuracy timing of critical agronomic practices and approaches to various marketplaces. This will require the Government to enhance its soil collection and analytical capacity to include, in the first instance, selected crops within specific ecological zones.

A further possibility is the collection of appropriate activity data throughout (but particularly at the production segments) selected value chains, to facilitate the development of “traceability” models: a prerequisite as Guyana expands its production for its robustly expanding hospitality sector and for CARICOM and other export markets.

At the autonomous level, as Guyana, for climate change reasons, is moving southwards, away from the “threatened” coastlands, there is need to rapidly regularise occupancy to facilitate development plans. Drones are appropriate for this activity. However, the appropriate legal framework must be established, operationalised and institutionalised. Drones may also be used for planning the layout, including planting densities, of medium to large sized farms, growing corn, soybeans, rice, sugar, tree crops, and pasture grasses. Similarly, they can be used for pest control.

In the Intermediate and Rupununi Savannahs, whose topography is generally flat and/or undulating, appropriate planting, fertilising and harvesting, autonomous machines can be adapted and used. Naturally, this will depend on the capital cost and the ability to maintain an acceptable level of Return on Investment. These activities could serve as pilots for similar enterprises in Belize and Suriname and, in a more limited way, Jamaica. That is, with its favourable oil and gas revenues, Guyana can be the leader in the use of AI in Agriculture in CARICOM.

Clearly, there are challenges to its use and these will be addressed in a subsequent article. However, suffice it to say that the successful use of AI, in ensuring long term resilient and consequently sustainable food systems and food security in Guyana, depends on the adequacy and competency of its HI, Human Intelligence.

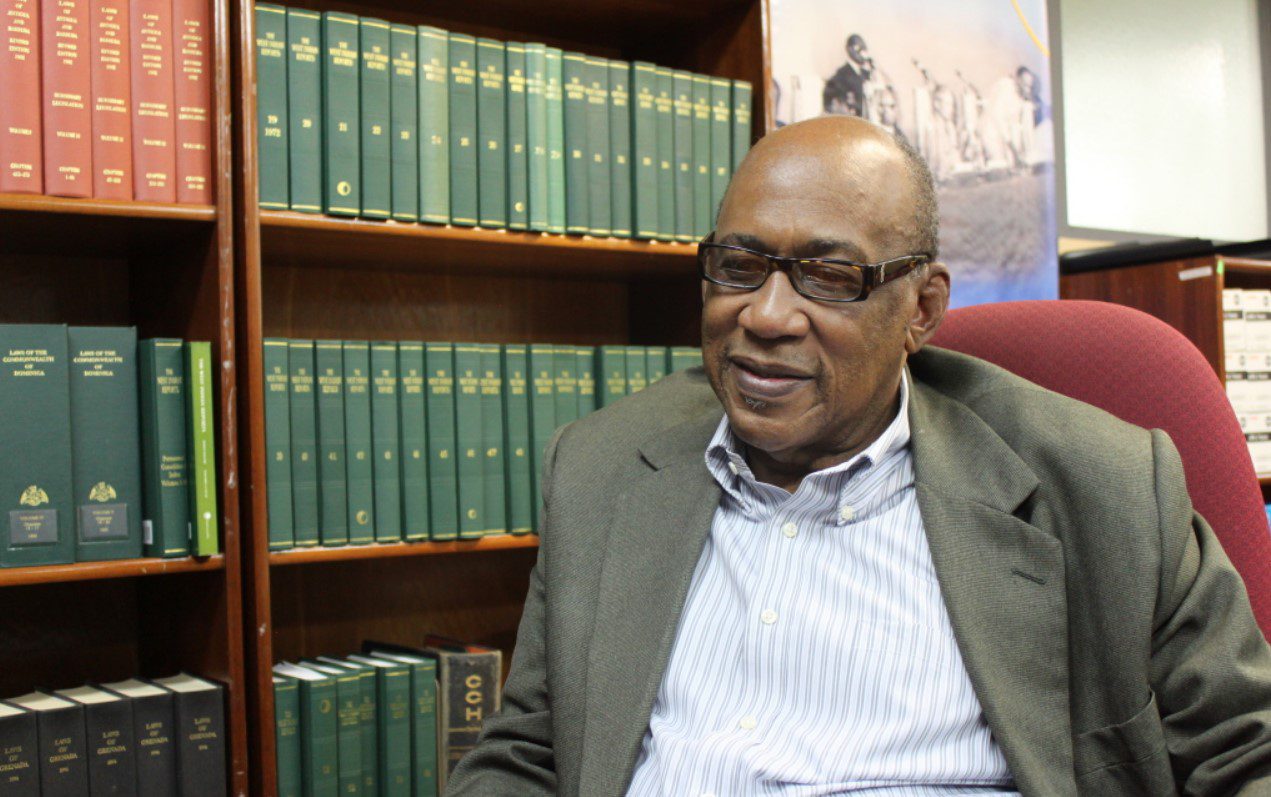

About the Author

Dr. H. Arlington D. Chesney is a leading Caribbean agricultural professional who has served his country, the Caribbean and the hemisphere in the areas of research, education and development. He’s a professional Emeritus of IICA and, in 2011, was awarded Guyana‘s Golden Arrow of Achievement for his contribution to agricultural development in Guyana and the Caribbean.