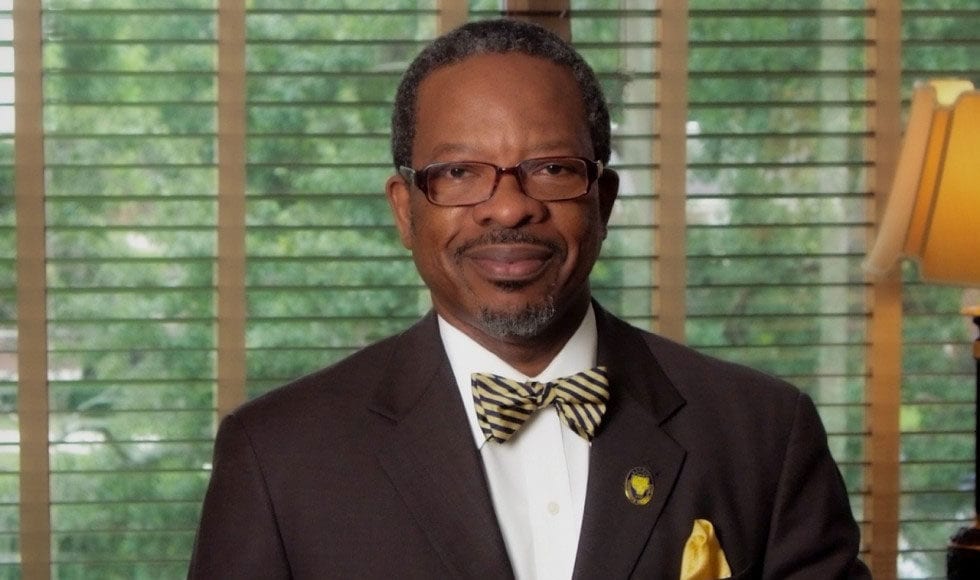

By Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued its latest ruling in the ongoing judicial saga between Guyana and Venezuela on April 6, last, during the week when three of the world’s most influential religions—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—were either celebrating or beginning to celebrate high holy periods: Easter for the Christians, Ramadan for the Muslims, and Passover for Judaism’s adherents.

As this writer listened to—and later read—the ruling by ICJ President, American-born Joan Donoghue, even though the entire drama isn’t concluded, the biblical tale of David and Goliath came to mind. The story is told in the Old Testament book of Samuel of the underdog battle between a young, diminutive shepherd David and giant, aggressive warrior Goliath, in which David defeated Goliath with weapons considered to be of dubious utility given the enemy’s weapons and armour. David wielded a slingshot and stones.

The Run up, the Vote

But before addressing the April judgment, it’s useful to note the run up to it. Recall that Guyana referred the controversy about the validity of the 1899 Arbitral Award to the ICJ in 2018 after several resolution efforts over many decades were futile. In accordance with its rules, the ICJ needed to ponder whether it had jurisdiction to hear the matter. In December 2020, the Court decided that it did, indeed, have the relevant jurisdiction, and in March 2021 Guyana was given until March 8, 2022, to submit its Memorial (case brief), which it did. Venezuela was granted until March 8, 2023, to present its Counter-Memorial. All things considered, the decision on the substantive case was expected to be made by March 2024.

However, Venezuela adopted a different legal/judicial strategy. Rather than work on its Counter-Memorial, in June 2022 the Bolivarian Republic filed preliminary objections to the admissibility of Guyana’s petition. Under ICJ rules, the trajectory of the substantive proceedings was suspended, and Guyana was then granted until October 7, 2022, to file a response to the objections, following which the Court held hearings on the matter from November 17 through November 22, last. The essence of Venezuela’s objections was that since the United Kingdom was a party to the 1899 Arbitral Award, it is, therefore, an indispensable third party to the case and the Court cannot adjudicate the matter without its consent.

In its 29-page judgment, the 15-member judicial organ of the United Nations system, noted that “the practice of the parties to the Geneva Agreement further demonstrates their agreement that the dispute could be settled without the involvement of the United Kingdom.” More substantively, the jurists noted “the Court concludes that, by virtue of being a party to the Geneva Agreement, the United Kingdom accepted that the dispute between Guyana and Venezuela could be settled by one of the means set out in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations, and that it would have no role in that procedure. …. The preliminary objection raised by Venezuela must therefore be rejected.”

Thus, by a 14-1 vote, the Court rejected Venezuela’s preliminary objection, and by the same vote, it found that it can adjudicate upon the merits of Guyana’s claims. The sole judicial dissent was cast by Judge Phillippe Couvreur, who Venezuela had appointed as an ad hoc jurist in the case. In effect, his was a sympathy vote. The effect of the April 6 Court decision is that the case trajectory is being restored, with a modification. Assuming that Venezuela will remain party to the proceedings, it now has until March 8, 2024, to submit its Counter-Memorial. A decision on the substantive case should be forthcoming within a year afterwards.

Legal/judicial slingshot

Unsurprisingly, the authorities in Caracas derided the decision, with Executive Vice President Delcy Rodríguez asserting that “the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela does not recognize the judicial mechanism as a means of resolving the aforementioned dispute” and that “the 1966 Geneva Agreement is the only valid and current instrument to resolve the dispute” through “direct political negotiations for the sake of a practical and satisfactory solution.” With these statements, Venezuela seems to be setting the stage for a repudiation of the Court’s final decision if it favours Guyana, which is a distinct possibility. The implications of repudiation extend way beyond the purview of the two immediate judicial parties and will be the subject of a subsequent discussion.

Venezuela’s exasperation over the April 6 decision must surely be driven by the fact that it’s the second loss before the Court; the first was in December 2020, when the Court rejected them and affirmed having jurisdiction in the matter. Moreover, Guyana’s continued petro-power successes most likely are playing mind games with the political elites in Miraflores Palace, the center of Venezuelan political power. In this respect, February 24, marked a milestone with production of 400,000 barrels of oil that day, heading to the desired 1 million barrels per day before the end of this decade. The elites there must also be frustrated that “little Guyana” is chalking up continuous victories before the World Court despite their superior resources. For instance, while Guyana fielded a team of 15 legal advocates, diplomats, and political operatives led by Agent and former Foreign Minister Carl Greenidge for the April 6 delivery at The Hague, Venezuela amassed twice the number—32—of legal scholars, diplomats, and political heavyweights, led by Agents Executive Vice-President Rodríguez and Ambassador to the United Nations Samuel Moncada Acosta.

Venezuela dwarfs Guyana in several crucial respects. While Guyana has a landmass of 214,969 sq km and a population of about 780,000, Venezuela boasts a size that’s more than four times that of Guyana—912,050 sq km—and a population of 28 million, which is 36 times that of Guyana’s. On the military front, Guyana’s security establishment of barely 5,000 soldiers pales in comparison to that of its neighbour, which exceeds 120,000 active personnel. Moreover, with proven oil reserves of 11 billion barrels equivalent, Guyana is far out-matched in petro-power potential by Venezuela, which has proven reserves of more than 300 billion barrels equivalent and ranks as the world’s number one oil reserve holder. Yet, when it comes to the judicial front, it appears we have a David and Goliath line-up where David is using a legal/judicial slingshot to vanquish his bigger and stronger challenger.

Guyana is on a petro-power roll. The week following the ICJ decision, the Prosperity, the third oil production ship, known formally as a Floating, Production, Storage, and Offloading (FPSO) vessel, arrived in Guyana from Singapore. Prosperity has a 220,000 barrels per day initial capacity and will boost Guyana’s daily production to about 600,000 barrels a day by the end of next year, inching closer to the goal of 1 million barrels per day by the end of the decade.

Inevitably, the country’s continuous oil successes will lead to enhanced economic and geopolitical profiles, not just regionally, but internationally. For example, earlier this month Guyana received the endorsement of all 32 members of the Group of Latin American and Caribbean States (GRULAC) at the United Nations for its candidacy for a seat at the UN Security Council in 2024-2025. South America’s sole anglophone republic is poised to secure the seat when elections are held in New York this coming June and will likely serve in the exalted principal organ of the United Nations System.

Coincidentally, the ICJ decision on the substantive case is expected during the very time Guyana is serving on the Security Council. Thus, things could be awkward for Venezuela, especially if Caracas contemplates repudiating the ICJ decision if it favours Guyana. It is important to consider options Guyana and the international community could pursue in that eventuality. This will be the subject of consideration in a subsequent series.

About the Author

Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith, a former Vice Chancellor of the University of Guyana, is a Fellow with the Caribbean Policy Consortium and Global Americans. His next book, Challenged Sovereignty: The Impact of Drugs, Crime, Terrorism, and Cyber Threats in the Caribbean, will be published by the University of Illinois Press.