By Dr. Meredith Arnold McIntyre – OilNOW

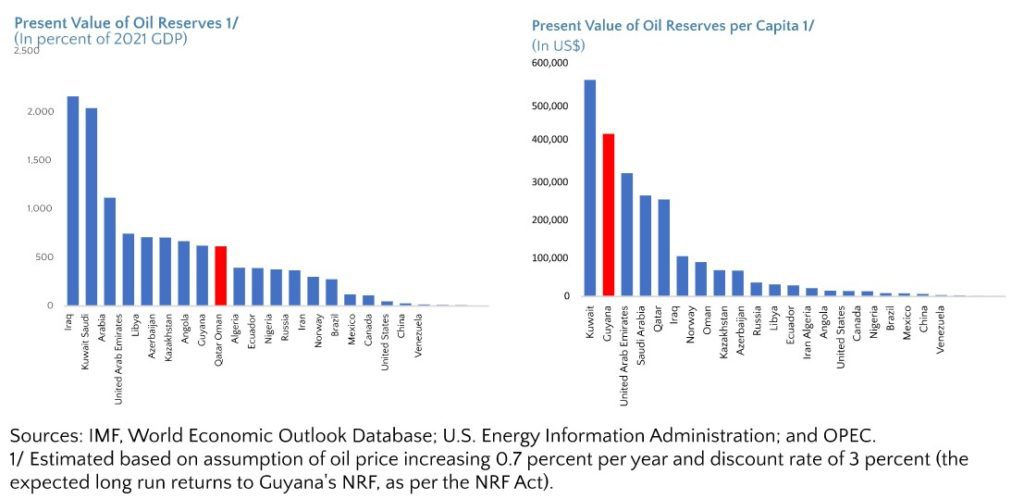

Guyana’s medium-term prospects are highly favourable and driven by fast expanding oil production. To date, international oil producers have discovered 11 billion barrels of commercially recoverable oil and gas that promise to transform Guyana’s economy from one based on agriculture and mining into a large oil producer, particularly considering it is a nation of about 790,000 people. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) presents estimates of the Present Value of Guyana’s oil reserves in percent of 2021 GDP. The data (chart 1) indicates that the present value of Guyana’s oil reserves (percent of 2021 GDP) per capita is only surpassed by Kuwait. In short, this is a large resource find that will generate substantial economic rents to be spent on a small population. The key policy challenge is the management of natural resource wealth ensuring that intergenerational savings are prioritised, and that public spending strengthens economic capacity and improves the standard of living and quality of life of the population.

Natural ‘Resource Curse’ and ‘Dutch Disease’

‘Dutch Disease’ occurs when a resource boom reduces the internal incentives to produce, and/or the international competitiveness of, domestically produced non-resource tradable (exportable and importable) goods. With the resource boom, ‘Dutch Disease’ can occur if spending increases significantly and runs up against absorptive capacity constraints that results in higher prices or inflationary pressures leading to a revaluation of the real exchange rate and over the medium-term a loss of international competitiveness in the non-resource tradable sector and its subsequent decline.

Therefore, a key policy challenge is the pace at which to ramp up public spending to meet legitimate development needs, for example, closing infrastructure gaps and achieving sustained improvement in social indicators – education and health. Economic policymakers must establish policy frameworks that ensure fiscal and debt sustainability and maintain price stability to support stronger growth.

Guyana’s Fiscal Policy Framework

Conventional wisdom suggests that with large natural resource windfalls, countries face a choice between intemporal savings to provide income security for future generations and increased spending in the near term to meet legitimate societal needs. Guyana has been a low-income country, but with the substantial increase in GDP, it has graduated to middle income status. However, Guyana’s human development has lagged the Caribbean region. The IMF reported in 2019 that a World Bank report suggests that Guyana’s human capital is lower than the median for its region and income group. Guyana’s human capital index (HCI) is 0.49, below the medians in the Caribbean (0.50) and Emerging Market Developing Economies (EMDE) (0.51).

Given the significant development needs, Guyana’s fiscal policy framework needed to appropriately include increased spending on the social sectors and to close infrastructure gaps while emphasizing intertemporal savings. One recommended option would be to have roughly equal shares of saving versus spending of the oil income in the medium-term (3-5 years) and as oil revenues substantially increase over the long-term and development indicators improve, greater shares could go to savings.

The Guyana government has been prudent in managing its natural resource wealth consistent with conventional wisdom, emphasizing the importance of increased public spending to meet development needs while building savings for future generations and to provide a buffer to external shocks, for example, volatile oil prices. A Natural Resource Fund Act (2019) that governed the management of natural resource wealth was amended by the new administration and the amendment contained several desirable features including: First, provisions strengthening transparency and accountability including removing extensive powers from the Minister of Finance and vesting them in a new Board of Directors, requiring that all reports and receipts of all petroleum revenues be published in the Official Gazette and the Minister of Finance could face up to ten years imprisonment if he fails to disclose the receipt of any petroleum revenues received by Government in the Official Gazette within three months of receipt of such monies.

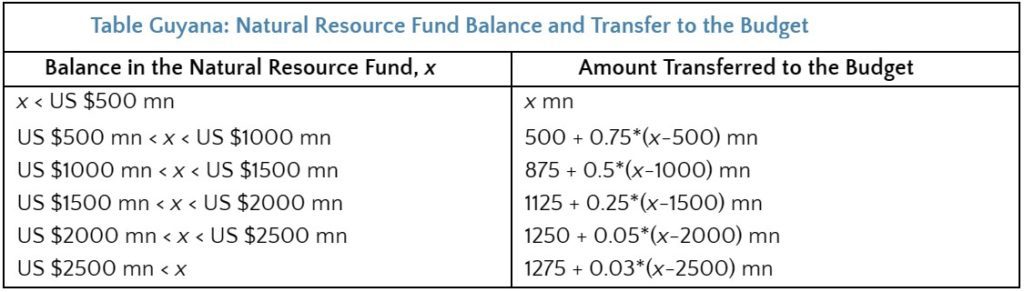

Second, the amendment introduces a simple formula for the transfer of oil revenues to the budget that is easily understandable by the public. The Bill allows the government to withdraw the entire amount in the NRF in 2022. Note the authorities went through a deliberative and consultative process on the NRF before proposing amendments and did not withdraw funds in 2021 while the process was ongoing.

Going forward, after the first withdrawal, the proposed legislation sets out a ceiling on withdrawals, with a progressively smaller proportion of the balance in the NRF being allowed to be transferred to the budget for public spending, and the remainder of the petroleum revenues is accumulated as savings in the NRF. More specifically, in any given year, US$500 million can be withdrawn and then a reducing percentage of what remains, starting with 75% from the second five hundred million; 50% from the third five hundred million; 25% from the fourth five hundred million; 5% from the fifth five hundred million, and then 3% from any amounts in excess of US$2.5 billion (see table below).

The government is committed to containing the fiscal position over the medium term to ensure spending is increased in a measured way to meet human development needs while preserving overall macroeconomic stability. Annual budgets are set over the medium-term within a fiscal framework that constrains the annual non-oil overall fiscal deficit (after grants) to not exceed the expected transfer from the NRF, that is a fiscal transfer rule.

Note, Guyana’s windfall is large enough to support increased spending without resorting to debt accumulation. In the near term, this strategy will anchor fiscal policy and ensure that fiscal spending increases at a measured pace to address development needs without resulting in macroeconomic imbalances, including a loss of competitiveness and an appreciation of the real exchange rate due to a significant increase in prices in the non-tradeable sector, that is, ‘Dutch Disease’.

However, Guyana is still in the process of crafting a fully spelt out medium-term framework with clear targets to anchor annual budgets. The experience of other oil producing countries e.g., Ghana, demonstrates that annual budgets that are not crafted in the context of a medium-term framework tend to result in negative macroeconomic outcomes and instability. An effective medium-term framework is needed to support the fiscal transfer rule that is aimed at achieving a zero overall balance target. In apportioning between capital and current spending, policymakers should consider the impact on the economy’s productive capacity. Empirical studies by the IMF indicate that a 1 percent point (ppt) increase in capital spending would have a more positive impact on real GDP growth than a similar increase in current spending in the medium-term (3-5 years). Capital expenditure spending could prioritise increasing connectivity with road expansion and rehabilitation together with increasing electrification to support a growing economy. Capital spending should be guided by absorptive capacity constraints to avoid ‘overheating’ the economy. Current spending would focus on increasing the access to and quality of education and health. Expenditures on the social sectors should be increased in line with non-oil GDP to ensure spending is not outstripping increases in GDP.

In summary, Guyana’s rapidly growing oil sector is resulting in substantial oil revenues that are potentially transformative, allowing increased spending to close infrastructure gaps and meet human development needs. The government has appropriately emphasized intertemporal savings and increased spending for the use of oil revenues. A simple, transparent formula has been implemented for the transfer of oil revenues from the NRF to the annual budget and this can ensure spending does not run up against absorptive capacity constraints and result in inflationary pressures and macroeconomic instability. However, the fiscal framework would further benefit from the adoption of a medium-term framework with well-defined targets guiding the design of annual budgets and an effective long-term fiscal anchor.

About the Author

Dr. Meredith Arnold McIntyre has been an economist for over 30 years. He has worked in a variety of Caribbean regional institutions including the Caribbean Development Bank, Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, and the Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery in the 1990’s. Dr. McIntyre joined the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in February 2001 and worked on countries in Africa and the Caribbean including leading IMF country team missions to Guyana. Dr. McIntyre has published a book and a variety of articles on issues in macroeconomic and trade policy in small states. He is currently an Associate, Manchester Trade Ltd and a Fellow with the Caribbean Policy Consortium.