By Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith – OilNOW

In light of recent developments in the border controversy between Guyana and Venezuela, I thought it worthwhile to expound on the newest tactics in Venezuela’s intimidation playbook. In Part 1, I examined two questions. First, what exactly is the latest bullying attempt? Second, why this latest Playbook effort? In Part 2, attention is paid to two other key queries. What are some earlier playbook pursuits, and can Venezuela be made to stop the bullying? This third missive centers on the latest intimidation developments and their implications.

Referendum and military bases

This past September, Venezuela’s National Assembly approved a resolution to hold a referendum intended to “allow the Venezuelan people to express their views on a significant territorial controversy – Venezuela’s claim over the Essequibo territories.” Jorge Rodríguez, president of the National Assembly, argued that the referendum would provide an opportunity for Venezuelans to “demonstrate and reiterate their commitment to defending the Essequibo in the face of attempts to violate the integrity of the national territory.”

One month after passage of the National Assembly resolution—on October 23, 2023, to be exact—Venezuela announced that the five-part referendum will be December 3, 2023. Among other things, Venezuelans will be invited to reject the 1899 arbitral award, approve of the 1966 Geneva Agreement as the sole binding mechanism to resolve the controversy, and repudiate the International Court of Criminal Justice’s (ICJ) jurisdiction in the matter. Moreover, the referendum will ask for agreement about creation of a new state encompassing more than 50% of Guyana’s current landmass, to be called Guayana Esequiba, while granting Venezuelan citizenship and identity cards to Essequibo residents, along with “accelerated social programs.” Additionally, on November 1, 2023, the country’s Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice pronounced positively on the constitutionality of the questions for the referendum.

Understandably, Guyana firmly rejected this move, with the ruling party and the parliamentary opposition joining in a patriotic embrace to meet this latest intimidation development. President Irfaan Ali and Opposition Leader Aubrey Norton joined by their respective delegations, met and issued a joint statement in which they condemned “the flagrant violation of the rule of law by Venezuela” and agreed to spare no effort to resist the Bolivarian Republic’s “persistent endeavors to undermine Guyana’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Further, the two leaders saw the necessity for a “vigorous and comprehensive public relations program and a proactive and robust diplomatic effort aimed at blunting Venezuelan propaganda and misinformation.” A few years ago, I sounded the alarm for Guyana to pursue imperatives related to public education, diplomacy, and enhanced security.

Moreover, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) contended—and quite rightly so—that Venezuela’s planned plebiscite has no standing in international law, although it can serve to undermine peace and security in the region. Commonwealth Secretary-General Patricia Scotland also repudiated Venezuela’s posture, restating the organization’s “firm and steadfast support for the maintenance and preservation of the sovereign and territorial integrity of Guyana, and the unobstructed exercise of its rights to develop the entirety of its territory for the benefit of its people.”

Guyana felt compelled to go beyond issuing declarations and galvanizing the support of friendly states and international entities. On November 1, 2023, the government filed an urgent request for provisional measures with the ICJ, asking the Court to issue an Order that prevents Venezuela from taking any action to seize, acquire or encroach upon, or assert or exercise sovereignty over, the Essequibo region or any other part of Guyana’s national territory, pending the Court’s final decision of the case about the validity of the 1899 Arbitral Award that’s currently before it. The urgency of the matter has prompted Guyana to ask the ICJ to schedule oral hearings on its request at the earliest possible date before the referendum’s December 3, 2023, date.

Yet, even as Venezuela was tapping into the intimidation playbook planning the December referendum, it was rolling out elements of psychological warfare, with military maneuvers near Guyana’s border and construction, beginning this past October, of a military airstrip in the La Comorra section of the State of Bolivar in the southeast of Venezuela, which abuts Guyana to its west. All this begs the question: What are some of the implications of these latest intimidation moves?

Audacity? Annexation?

These latest developments, building on earlier ones, have a multiplicity of dangerous implications—fitting into at least four areas: security-geopolitics, political-psychological, economic, and diplomatic-international legal. Understandably, not all areas could be examined here, or even all aspects of the ones discussed. Thus, attention will be paid here to some aspects of security-geopolitics.

The planned referendum and construction of military bases present just as many security-geopolitics red flags as a Chinese Communist Party people’s parade. The danger signals are glaring about Venezuela’s stage-setting in three inter-connected areas: whipping up nationalist sentiment to position President Nicolás Maduro to retain power when presidential elections are held next year; skepticism about prevailing at the ICJ and, therefore, positioning the country to repudiate the Court’s decision; and psychological and security preparation for the possible annexation of the Essequibo, perhaps to induce Guyana to come to the bilateral negotiation table, a long-held aim.

The audacity of annexation would be a death-knell for Guyana as a nation and it would create multiple geopolitical ripples involving Brazil, the United States, China, Colombia, Britain, the CARICOM, the Commonwealth, the Organization of American States (OAS), and the United Nations, among other state and international entities. Keep in mind that a revision of the frontier between Guyana and Venezuela would require revision of Brazil’s borders with both Guyana and Venezuela, as the Brazil-Guyana-Venezuela trijunction point was settled in 1932 as a result of the 1899 Award.

Remember, too, that Brazil, which has the world’s third longest land border, behind China and Russia, has borders with every country in South America except Chile and Ecuador, several of which have dispute elements; and that the United States, China, and Britain are among countries that have massive investments in the petroleum pursuits in both Guyana and Venezuela. Moreover, annexation would trigger activation of Article 4 of the treaty of the eight-member Regional Security System (RSS), Guyana having joined the RSS last year.

Article 4 specifies: “The Member States agree that an armed attack against one of them by a third State or from any other source is an armed attack against them all, and consequently agree that in the event of such an attack, each of them, in the exercise of the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will determine the measures to be taken to assist the State so attacked by taking forthwith, individually or collectively, any necessary action, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the peace and security of the Member State.”

Security Council trigger and migrant factor

Annexation also would trigger action by the United Nations Security Council, with the likelihood that Russia would assume the role of protector of Venezuelan interests with the United States protecting Guyanese interests, taking geopolitical gamesmanship to the global stage. China likely will try to stay neutral.

Quite importantly, in terms of the posture of global and hemispheric powers, both the United States and Brazil restated their staunch support for Guyana at the November 1, 2023, meeting of the OAS Permanent Council. Notable, too, Alistair Routledge, president of ExxonMobil Guyana, has stated plainly that the oil giant is not intimidated by the Venezuelan moves, and he has assured Guyana and the world that ExxonMobil will continue its business dealings with the Guyana government once the terms are favorable to them. Thus, all things considered, occupation is not probable. But it is not beyond the realm of possibility. Consider the following.

First, it would not be the first time that Guyana was a victim of annexation, although the first episode was miniscule compared to a grab of the entire Essequibo. Recall that one of the earlier bullying actions reported by Guyana in its March 2018 submission to the ICJ was the action in October 1966, when the Venezuelan military seized the eastern half of Ankoko Island in the Cuyuni River, on the Guyana side of the boundary created by the 1899 Award and the subsequent 1905 Agreement. Later, they built military installations and an airstrip there. Guyana has not been able to evict them.

Second, President Nicolás Maduro has been a staunch supporter of annexation efforts elsewhere. Indeed, he was one of the first—and few—world leaders to embrace the Russian invasion of Ukraine, viewing Vladimir Putin’s action as justified to right a historic wrong. Third, the world’s preoccupation with Russia’s Ukraine foray and the Israeli-Hamas conflict could well embolden Maduro to consider those as sufficient distractions for him to move into the Essequibo. Finally, there’s the migrant factor. Since 2015, some 7.4 million Venezuelans–-about nine times Guyana’s entire population—have been displaced from the Bolivarian Republic. Thousands have fled across the border to Guyana, with between 24,000 and 30,000 men, women, children, and elderly seeking refuge in the Cooperative Republic, not just in border areas, but also, along the country’s Atlantic coast.

As could be imagined, this is causing myriad difficulties for the Guyanese authorities and citizenry, such that Rear Admiral (Ret.) Gary Best, former head of the country’s armed forces, recently flagged the national security implications of the influx and advocated placing caps on the number allowed in. Although one doubts that the migrants constitute a planned Trojan Horse by the Venezuelan political and military elites, their presence might well imbue confidence in Maduro that he has a natural—and national—constituency that could accommodate, if not actively assist, any annexation designs. For all this, one hopes that Maduro sees the annexation cost-benefit scales as balancing against him, making annexation possible, but not probable.

About the author

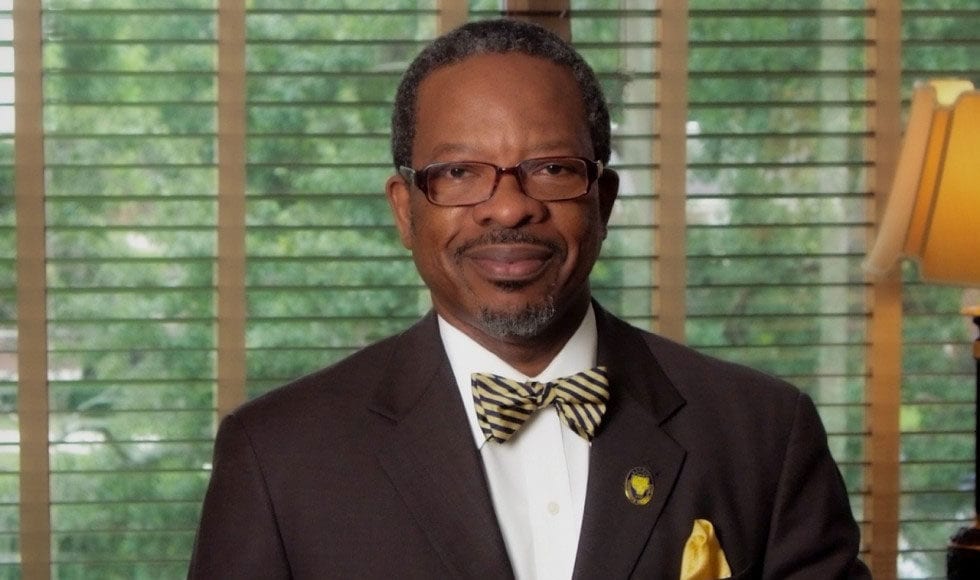

Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith, a former Vice Chancellor of the University of Guyana, is a Senior Associate with the Center for Strategic and International Studies as well as a Fellow of the Caribbean Policy Consortium and of Global Americans. The University of Illinois Press will soon publish his next book, Challenged Sovereignty: The Impact of Drugs, Crime, Terrorism, and Cyber Threats in the Caribbean.