Prime Minister Dr. Keith Rowley of Trinidad and Tobago finds himself at the intersection of geopolitical issues that place him and his country in a sensitive but crucial position. On one hand, he must navigate the growing tensions between Guyana and Venezuela over Venezuela’s renewed claim to Guyana’s Essequibo region. On the other, he must also consider his country’s economic interests in a collaborative gas venture with Venezuela, known as the Dragon Gas project.

The controversy between Guyana and Venezuela pertains to Venezuela’s claim to two-thirds of Guyana’s territory. Venezuela has even taken steps to conduct a national referendum on how to pursue this claim. This has generated significant concern among international bodies and neighboring countries. Among these are the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), to which both Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago belong. CARICOM has stated that the proposed referendum has “no validity, bearing, or standing in international law in relation to this controversy.” CARICOM unequivocally supports Guyana’s territorial integrity.

Rowley aligns himself clearly with CARICOM’s position. “Guyana is our neighbour, Venezuela is our neighbour. They are two friendly states. Guyana is part of CARICOM, and we have a CARICOM position on Venezuela. And I think that is where Trinidad and Tobago is,” the Prime Minister said during an October 26 press conference. As the lead Prime Minister in CARICOM’s quasi-cabinet on safety and security, Rowley’s agreement with the CARICOM statement is expected. But he now walks a tightrope, having to balance his defense of Guyana’s sovereignty with his own country’s economic interests.

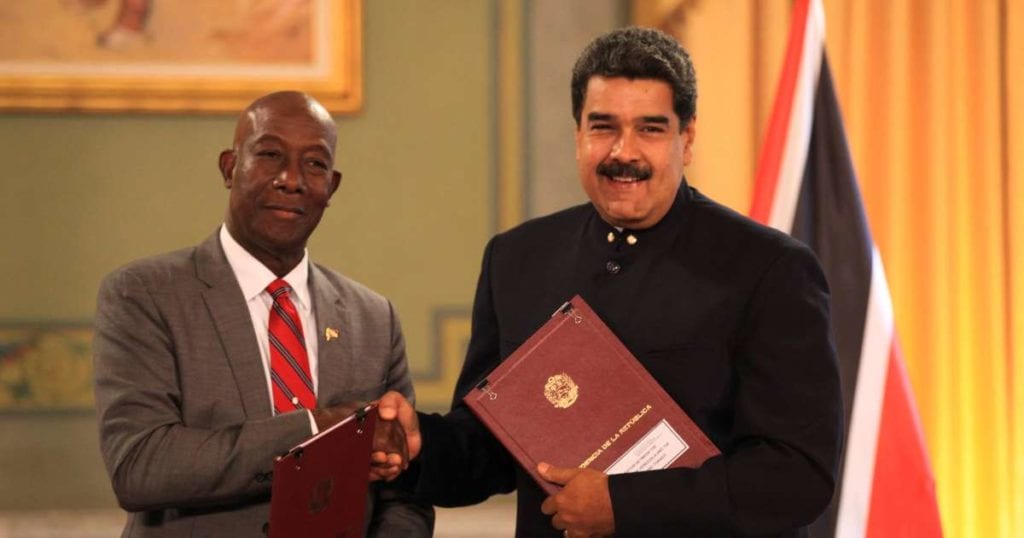

The Dragon Gas project holds significant economic potential for Trinidad and Tobago, promising to bolster the country’s declining hydrocarbon production. Asked about the possible impact of the Guyana-Venezuela conflict on the gas project, Rowley said, “I don’t see it as a close connection…” Nevertheless, he did not entirely rule out that the controversy could have implications, noting that “conflict always has potential to change courses of things.”

Rowley framed his support for Guyana not as a partisan stance but as one based on principle. He emphasized that Trinidad and Tobago’s foreign policy aligns with the fundamental tenets of the United Nations Charter. “The same principles that we use to protect Venezuela’s right to self-determination about its elections in the face of sanctions and threats of endangerment, those same principles we use now with Venezuela in its treatment of Guyana,” he stated. “We believe that our region is a zone of peace and we are all better off living in a zone of peace, respecting international law and respecting the rights of our neighbours.”

Managing these multifaceted issues is no simple task. Yet, by anchoring Trinidad and Tobago’s position in universally recognized principles and in alignment with CARICOM, Rowley sets a precedent for how smaller states can adeptly handle complex geopolitical issues with integrity and foresight.