A commonly held view first introduced by the Dutch Disease literature is that resource price increases and more of the resource discoveries lead to higher government spending, an increase in the relative price of non-tradable goods and a loss of competitiveness in the non-resources tradable sectors (Pieschacon 2012).

However, in a future small oil-exporting economy like Guyana, fiscal policy affects the extent to which Gross Domestic Product (GDP), private consumption and the relative price of non-tradable goods react to a typical shock to world oil prices. Furthermore, fiscal discipline seems to be a valuable tool to regulate the impact of oil price shocks: fiscal policies that insulate the economy from oil price shocks seem to be welfare improving over procyclical ones.

Therefore, for Guyana, regressive taxes such as royalties exist to satisfy policy objectives other than revenue maximization, such as achieving early revenues, while rent-based or profit-sensitive fiscal instruments must be designed with progressive marginal rates to maximize government revenues (Wen 2018). Hence, the emphasis should be placed on tax rate progression of the direct taxation of profit or rent, rather than progressivity in the overall government take (GT). However, as regressive taxes, by their very nature, tend to be distortionary, the optimal degree of progression in the rent- or profit-tax rates must take these distortions into account (IMF 2018).

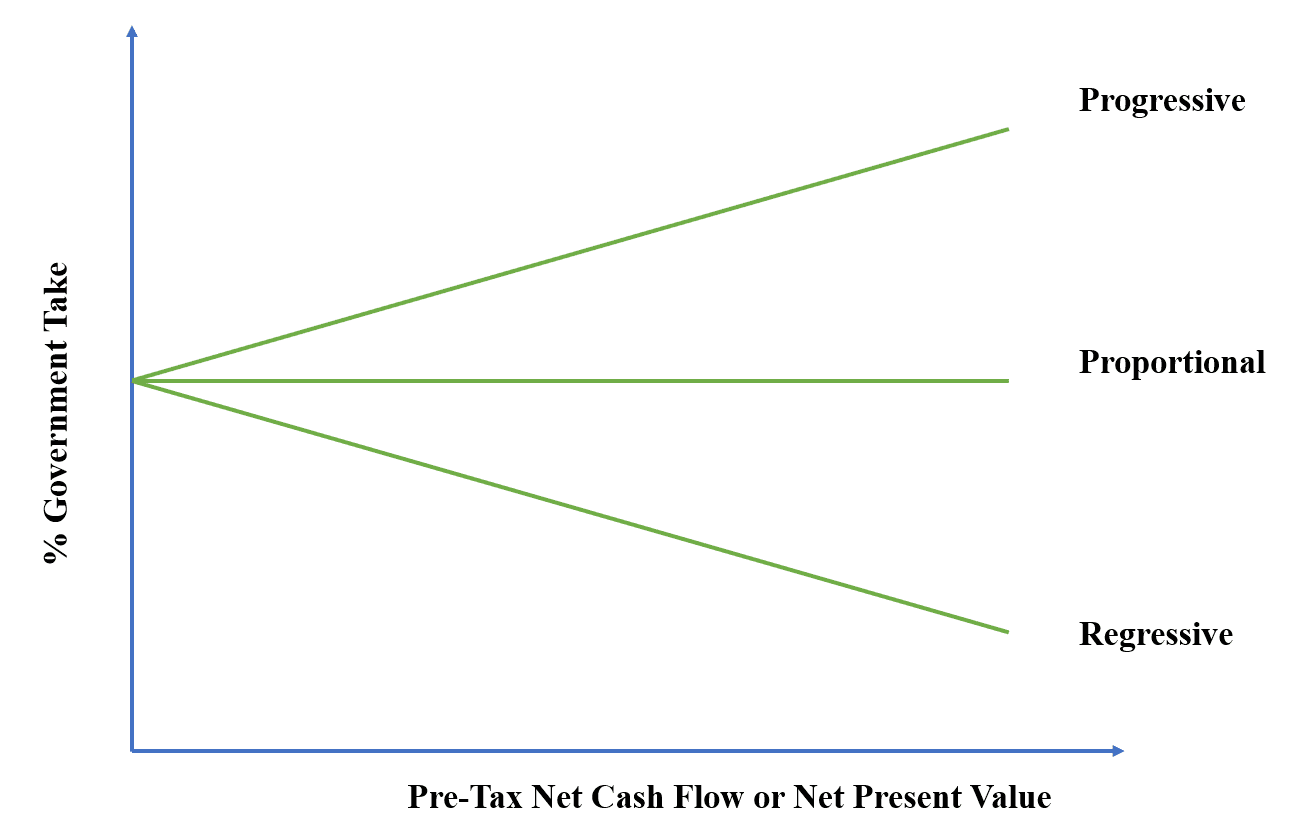

The principle that fiscal regimes for petroleum and minerals should exhibit progressivity is commonly advocated (Progressivity is one of the guiding principles of fiscal regime design in the International Monetary Fund’s Fiscal Analysis of Resource Industries (FARI) model). Progressivity refers to a rising government share of the net cash flows of a project, the government take, as the value of the resource increases.

Regressive taxes (the opposite of progressive), such as royalties, signature bonuses, and land rental fees, exist to satisfy various government objectives other than revenue maximization (It should be noted that royalties are typically paid as percentage of gross revenues, rather than as a percentage of profit). Such auxiliary objectives of fiscal regimes include generating tax revenues early in a project’s life cycle and ensuring revenues for the government even in the face of weakening economic conditions. Then, given the existence of regressive elements in the fiscal regime, the government’s primary objective of revenue maximization requires marginal tax rate progressivity in the design of its profit-sensitive fiscal instruments (Daniel 2010).

In this way, the progressive tax instruments enable governments to capture the rent ‘left on the table’ by the regressive instruments. However, by their very nature, regressive taxes tend to be distortionary taxes, and vice versa. In the presence of such distortions, profit-sensitive taxes themselves, even a direct tax on economic rent, cease to be neutral. As a result, the optimal degree of marginal tax rate progression of the profit-sensitive taxes must be considered in a best policy environment. The emphasis of tax policy evaluation is thereby shifted from achieving progressivity in the overall government take to setting an optimal degree of marginal tax rate progression in the direct taxation of profit or rent.

The higher the royalty rate, the more progressive the profit sensitive tax rate schedule should be, although the general level of the tax rates on profit must be lowered to accommodate a high royalty rate. The overall effect of a royalty, together with an optimal progressive rate schedule, is generally unclear and not necessarily expected to be progressive (Keen et al. 2014).

There are several other practical implications of this analysis. The first is that it is useful to determine separately the Average Effective Tax Rate (AETR) for the regressive and the progressive tax instruments to better visualize the performance of the profit-sensitive tax instruments for maximizing tax revenue, taken as a given the regressive instruments, whose existence is, presumably, not revenue maximization.

Moreover, a measure of the performance of the profit-sensitive tax rates is the ‘buoyancy’ or elasticity of total government take with respect to the changes in the economic rent generated by a project. If the resistance is close to one, it means that, as the rent increases, say, due to an increase in the price of the resource, the progressivity of the profit-sensitive instruments fully offsets the regressive elements of the fiscal regime and any windfall rent is captured as government revenue. In addition, since royalties exist mainly to ensure early government revenues, the royalties should be creditable (with an uplift for the time value of money) against profit taxes (or rent taxes) in the post-payback period. In this way, the government can achieve early revenues without compromising the objective of revenue maximization and, hence, the rate schedule for the profit taxes can be relatively flat, minimizing tax distortions.

Purposes of Progressivity

Types of Fiscal Schemes

Source: University of Aberdeen (2018)

Source: University of Aberdeen (2018)

It should be noted that a neutral progressive tax could be achieved with the progressive variant of the Resource Rent Tax (RRT) (Garnaut and Clunies Ross 1983). However, in practice, no host government has relied on resource rent taxes on their own. Instead, resource rent taxes are combined with other taxes and charges. Thus, in a royalty/tax regime (as in the current Guyanese case), a resource rent tax is typically combined with royalty and corporation tax. The onus is then typically placed on achieving progressivity with the full package of fiscal instruments. The practice has been to combine progressive taxes with these other taxes that provide revenue in the early stage. With such hybrid systems progressivity can still be achieved overall by offsetting the regressive elements through the introduction of sliding scale for example with royalties. Similarly, the desired objectives [including progressivity] can generally best be fulfilled by a mainly profit based tax regime incorporating an effective rent capture mechanism, with a limited role for royalties or cost recovery limits to reduce government risk and provide assurance of early revenues (Land 2010).

The underlying reason for recommending a progressive tax regime for natural resources are equity and flexibility or stability.

Equity

An analogy is sometimes made between progressive resource taxes and progressive personal income taxes. On the surface, the idea of an increasing profile for government take parallels the most commonly used definition of tax progressivity in personal income taxation, which is that a taxpayer’s average tax rate, i.e., a person’s tax bill as a share of income; should be an increasing function of personal income. Progressive personal income taxes are conceptually tied to notions of an equitable distribution of income or inequality aversion (Nakhle 2004).

Hence, the vertical equity principle of fairness in the context of resource taxation states that firms which exploit more valuable resources have a greater ability to pay and so their tax liabilities can be greater.

The analogy between a progressive profile for the AETR in natural resource taxation and progressivity in personal income taxes is tenuous. First of all, the investors in a resource project, as in the case in Guyana’s offshore fields are foreign shareholders. Hence, the government currently has no equity reason to provide tax relief on projects yielding only modest rent. Furthermore, a claim to high rents is neither necessary nor sufficient for high income at a personal level.

Finally, a tax on corporate profits may be shifted onto the consumers of natural resource products or on to the workers in the domestic resource extraction industry through equilibrium changes in market prices or wages. Thus, the equity argument for progressive personal income taxation does not readily extend to natural resource taxation. The only role for equity in this context is the fact that, as owner of the resource, a government is entitled to maximize its return on behalf of its citizenry. Maximizing the return depends on the overall AETR.

Flexibility and Stability

Ensuring the stability of a tax regime is the most commonly cited reason for progressively taxing resource rents. Stability means that the tax regime will not be subjected to political or bureaucratic pressures for renegotiation, when the economic conditions of a natural resource project change. Stability is achieved by making the regime flexible, in the sense that the tax rates adjust automatically with changes in circumstances, such as increases or decreases in the resource price.

Flexibility in rent collection is the capacity of fiscal instruments to collect a reasonable share of the resource rent over time under a range of future market outcomes and it should be noted that rent and profit-based taxes and state equity instruments rank more highly under this criterion since the government take tends to vary with project profitability. Similarly, the tax system should be designed with the flexibility to extract the different rents actually generated by deposits under dynamic conditions of price and cost on an ex post basis. This requires, in any individual project, that the higher the profitability of resource extraction, the greater the share of total benefits that accrues to the host country. Where this positive correlation exists, the fiscal regime is said to be progressive (Osmundsen 2010).

The adaptability of the system will also influence investor perceptions of risk. A system that responds flexibly to changes in circumstances may be perceived as more stable. Adaptability can be measured by indicators of progressivity.

Another reason for choosing a tailored tax system is the political constraints imposed by voter dislike of large profits and high dividends at private petroleum companies. A purpose of progressivity is to reduce the need for tailoring. The problem is that tax changes are made on an ad hoc basis. If progressivity is an important goal for the government, it would be better from that perspective to construct a clearly defined and stable progressive tax system. The flexibility/stability argument for tax progressivity appears sensible and grounded in experience.

A more progressive regime gives some relief to investors for projects with low rates of return, while allowing the government to increase its share of revenue when the investment is highly profitable. Thus, a more progressive regime could attract investment for marginal projects (increasing government revenue over time), just as a heavy early fiscal burden on a project could deter investment altogether.

Policy Implications

Whilst, the regressivity of certain widely used fiscal instruments provides a justification for having progressive components in the tax system, it is not a persuasive argument for progressivity in the overall proportion of rent collected by the government from a given resource project. In other words, disapproval of regressive fiscal regimes is not logically equivalent to support for progressive ones.

A tax regime with both progressive and regressive elements may still result in a constant value of the overall government take, i.e., government revenues that are proportional to the size of the economic rent.

Hence, an alternative perspective on progressive natural resource taxation is necessary for an emerging petroleum economy such as Guyana. Regressive taxes serve policy objectives other than tax revenue maximization. In this context, progressivity is an appeal to the government to ensure that profit-sensitive elements of the fiscal package are designed to capture the rent left over by the regressive taxes.

If the tax is progressive, then the detrimental impact of other imperfections in the tax system will not be magnified. For example, if the tax base includes part of normal profits then there will be a reduction in marginal field profitability. If the tax system is not progressive, then this reduction may be severe and development decisions on many fields may be jeopardised.

Therefore, the petroleum tax system as a whole should be progressive, rather than, for example, insisting that only the Petroleum Revenue Tax be progressive by introducing increasing marginal tax rates. As such, one recommendation for the Government of Guyana is to opt for a progressive Resource Rent Tax by 2020 and replace both, any imminent Petroleum Revenue Tax and the current Corporate Income Tax on the oilfield projects. A beneficial implication of a progressive tax system is that price signals to the developers of marginal fields will not be dampened. Progressivity refers to the tax take increasing as pure profits increase (at a more than proportional rate) which leaves marginal incentives unchanged. A tax levied specifically on rents would not distort incentives, regardless of whether it is progressive, proportional or regressive.

Further, it may be more appropriate for the government to receive a fixed proportion of the rent, albeit at a suitably high level. It is the progressive components of the fiscal regime, such as a resource rent tax, a corporate income tax, or the government’s share of profit oil, each designed with multiple tiers, that allow this to occur, by complementing the regressive components. The regressive elements may also occur ‘by accident,’ when there exist intangible forms of costs, such as managerial effort, which are unobserved by the government and hence are not deductible from the tax base (Lund 2009). The regressive elements distort the firm’s choice of inputs and reduce the size of the realized economic rent below its potential value.

In an optimal policy environment, the government, as a resource owner, should aim to capture as much of the economic rent as it can. Ideally it would capture 100 percent of it through its portfolio of progressive and regressive taxes. However, it must also be recognized that unobserved and non-deductible costs imply that the observed tax base for profit-sensitive or rent-based taxes may overstate the true size of the realized economic rent. For this reason, taxing nearly 100 percent of the observed economic rent is generally inappropriate in practice.

One way to calibrate the schedule of rent-based progressive tax rates is to determine what the tax rate would need to be at different prices of the resource, given the anticipated production and cost profiles of resource projects, such that the investors’ after-tax rate of return is held constant, at a rate deemed to be acceptable to investors. Then, all unanticipated increases in economic rent due, e.g., to price increases, would accrue to the government, implying an elasticity of revenue with respect to rent equal to one.

However, the tax schedule need not be expressed directly as a function of prices, but could, instead, be made to depend on commonly used profit indicators, such as the pay-back ratio. Indeed, if projects vary substantially in terms of costs and production, then it may be best to set the tax rate schedule as a function of a profit indicator, rather than price (Kemp 1975). Setting the tax rates directly as a function of price can prevent ‘gold-plating’ activities, whereby firms increase expenditures inefficiently, simply to reduce the indication of profitability. However, firms can still attempt to manipulate the fiscal regime under-price-based tax schedules, but only to the extent that they can time their expenditures, so that they occur when prices are perceived to be relatively high. Finally, tax credits, rather than tax deductions, for royalties and signature bonuses would help reduce the distortions caused by the major regressive elements of a fiscal regime. This would reduce the need for progressivity in marginal tax rates, and likely raise the overall level of government take.