(Bloomberg) The latest mission by OPEC and its partners to contain an oil glut is entering its most critical phase.

Saudi Arabia, Russia and other major crude exporters struggled to keep a surplus in check over the past six months despite cutting their production, and oil prices remain stuck below levels most need to fund their economies.

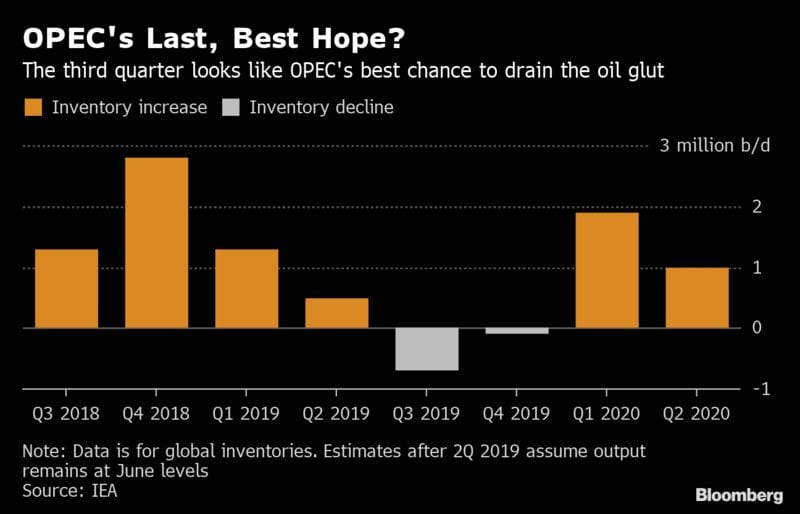

The coalition’s best chance to tame the oversupply may be this quarter, when oil demand hits an annual peak, before world markets enter a weak patch through the winter into 2020. If OPEC and its allies can’t deplete inventories, their primary measure of success, it’ll be hard to avoid the conclusion that their strategy is a bust.

“The third quarter is the optimal window to put a significant dent into global inventories,” said Michael Tran, a commodity strategist at RBC Capital Markets LLC in New York. “Otherwise the challenge facing OPEC of returning inventories back to equilibrium becomes an even taller task.”

The 24-nation alliance known as OPEC+, a union between the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and non-members that together pumps about half the world’s oil, has faced a tough job in trying to balance markets since it formed almost three years ago, as the ongoing American shale boom unleashes a wave of competing supply.

Their task has only grown harder this year with a slowing global economy and the U.S.-China trade war sapping fuel consumption. In response, OPEC+ has been implementing a production cut of 1.2 million barrels a day.

Mixed Results

The results for the first six months, however, were mixed, with stockpiles in developed nations unexpectedly swelling by 164 million barrels, according to the International Energy Agency.

Oil prices have consequently faltered. After rallying about 40% to more than $75 a barrel in London during the first four months, they have since retreated to stay below the level most OPEC nations require to cover government spending. Brent futures were near $63.50 a barrel on Thursday.

Whittling down inventories is OPEC’s top priority, Saudi Arabian Energy Minister Khalid Al-Falih, who represents the group’s biggest member, said at its latest meeting on July 1.

“It’s fair to say that over the last few months, inventories did build in a manner that we would like to avoid,” Al-Falih said at the group’s headquarters in Vienna. “Going forward, we’re going to bring inventories down. Ultimately, we measure our success by how we manage inventories.”

Window of Opportunity

If there is to be a turnaround in achieving that objective, it should be visible now.

Global oil demand is forecast to surge to a record high of 101.4 million barrels a day this quarter as American motorists take to the road for summer vacations, according to the Paris-based IEA.

By keeping output at current rates, OPEC should be able to slash global inventories by about 64 million barrels between July and the end of September, the IEA’s data indicate. OPEC’s own estimates point to an even sharper reduction in stockpiles, of about 149 million barrels.

There are signs that high summer demand is starting to take effect. Crude stockpiles in the U.S. declined by 10.84 million barrels last week in a sixth consecutive week of draws, the longest stretch since early 2018.

But after this quarter, the window of opportunity begins to close.

Demand for OPEC’s crude will ease in the fourth quarter and then retreat sharply in early 2020 as U.S. shale production continues to soar, the IEA predicts. The organization’s current output is almost 2 million barrels a day higher than the level needed in the first quarter of next year, IEA data show.

“The second half of 2019 might be OPEC’s last best shot at tightening the market before the supply glut emerges in 2020,” said Ed Morse, head of commodities research at Citigroup Inc. in New York.

Unplanned Losses

Still, the situation for OPEC may not be as bad as it looks. Although the IEA’s data implies that global stockpiles accumulated substantially in the first half, storage levels reported so far by consuming nations show a far more modest increase, said Giovanni Staunovo, an analyst at UBS Group AG in Zurich.

OPEC could also receive other assistance in the months ahead.

Over the past three years, the cartel’s efforts to restrain output have been amplified by unplanned supply losses in some members, particularly Venezuela and Iran, which effectively doubled the size of its intended cutbacks.

As political tensions flare in the Persian Gulf, where Iran has been accused of attacking oil tankers while U.S. President Donald Trump pressures the country with financial sanctions, the risk of further disruption persists. The economic unraveling that has battered Venezuela’s oil industry is also showing few signs of recovery.

Deeper production losses in those countries, or in other unstable OPEC members like Libya and Nigeria, may once again help keep supplies in check.

But with output in Iran and Venezuela already at the lowest in decades, it could be that OPEC has already received all the accidental help it’s likely to get for now.

That may leave the group with little choice but to cut production further — an option so far rejected by Al-Falih — or admit defeat.

“I doubt OPEC+ can implement a big enough stock draw in the third quarter to offset the supply tsunami coming next year,” said Bob McNally, president of Rapidan Energy Group and a former oil official at the White House under President George W. Bush. “And if a recession hits, or Trump strikes a deal with Iran, it’s game over for OPEC no matter how big the third-quarter draw.”