(Wood Mackenzie Analysis) The coronavirus outbreak has derailed OPEC+, thrown the oil market into turmoil and sent an already unloved sector into freefall, setting in motion a chain of events that led to the biggest fall in the oil price in 30 years. While the long-term impact on demand and commodity prices is still unclear, it is obvious that current prices are bleak news for the sector. As the price rout deepens, the oil and gas sector is back into survival mode.

How will the oil price crash hit upstream spending?

The upstream oil and gas sector faces unprecedented uncertainty. The range of outcomes for investment is very wide, but it is clear oil companies must act quickly. There are strong parallels to 2015-16, but the macro-environment is very different this time. Even if OPEC+ returns to the table and comes to a new agreement, recent events have irreversibly changed the perception of risk. The genie will not be put back in the bottle.

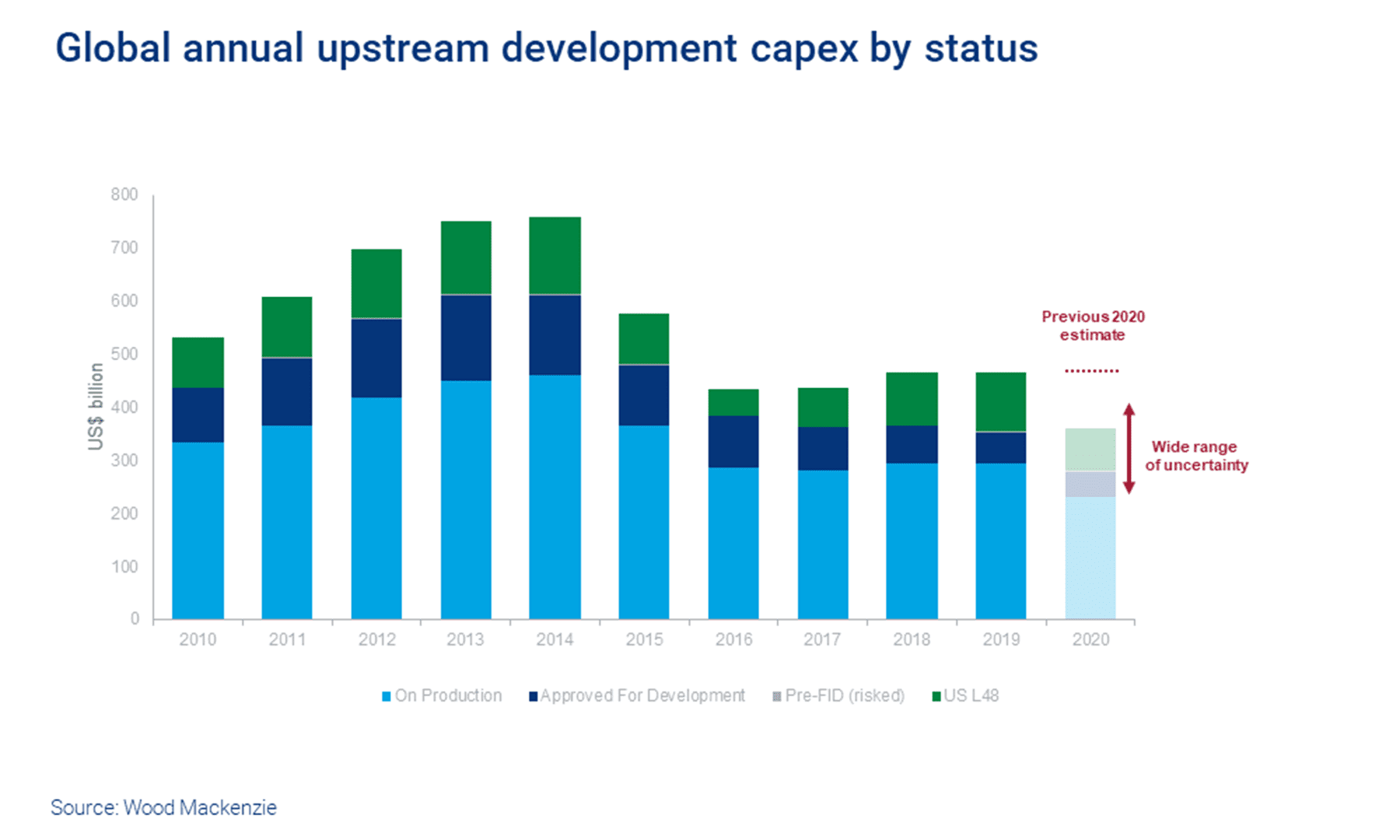

How will the industry respond to such uncertainty? Cuts to discretionary investment will be immediate and deep. Global spend could fall by well over 25% year-on-year. This estimate will change as more data becomes available.

To improve their chances of survival at low prices, companies have three main levers to cut expenditure:

- Drive efficiencies to extract the same or similar production for lower investment;

- Defer the sanction (FID) of new projects;

- Reduce activity levels and costs in the base business (including short-cycle investment, exploration and operating costs).

Large new projects will be put on hold and short-cycle discretionary investment will be dialled back to the bare minimum. Spend on projects under development and onstream will also be targeted. Exploration will be trimmed; operating and other fixed costs face intense scrutiny.

Only the lowest-cost producers with the strongest finances will be in a position to make meaningful discretionary investments. Any decision to follow Saudi and Russia and grow output will likely be driven by policy rather than economics.

How low can the price go before different sources of production become uneconomic?

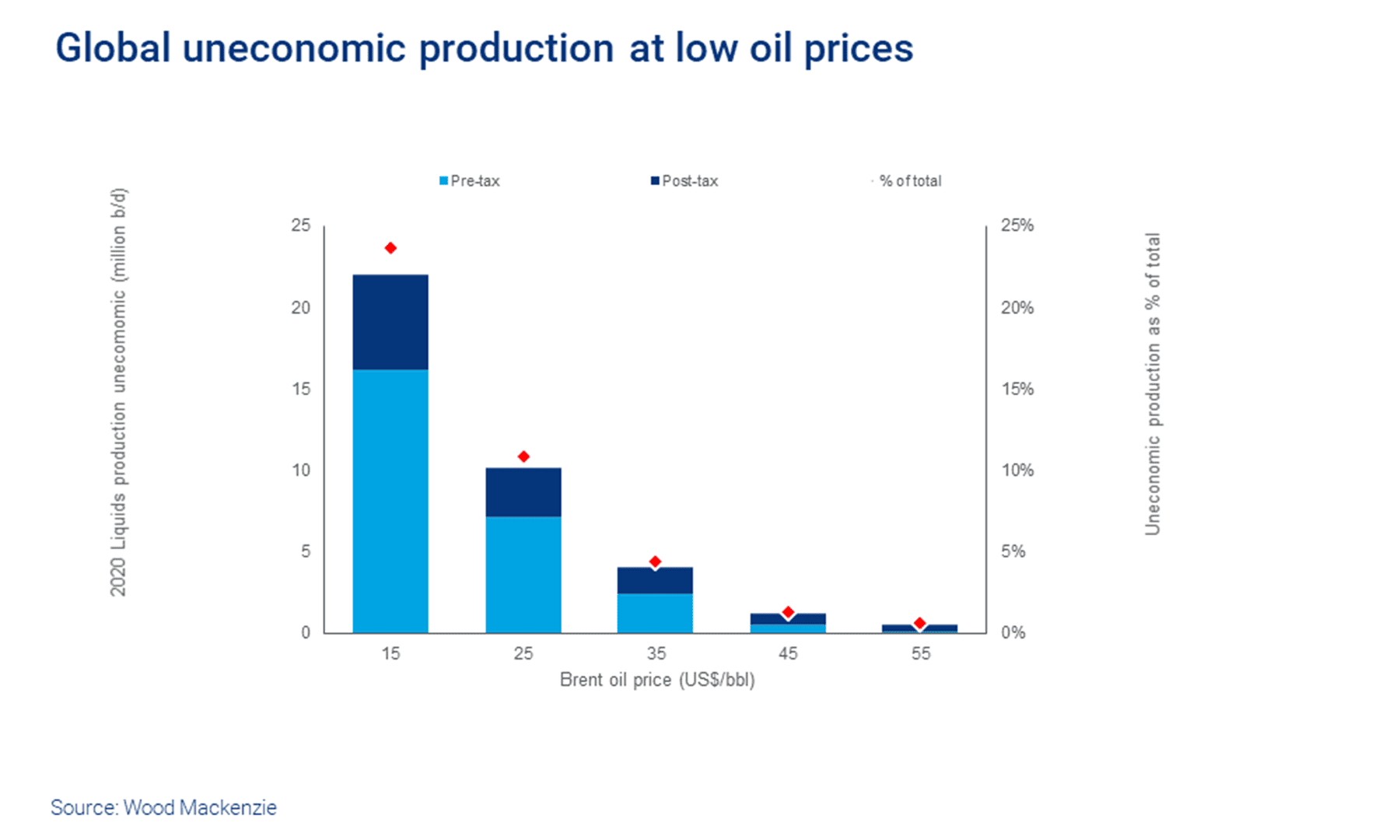

If prices do not rebound quickly, we’ll see a significant impact on currently producing fields and future supply. Our supply analysts have modelled price scenarios to discover how low the price can go before different sources of production become uneconomic, where production shut-ins are most likely, and whether governments influence the outcomes.

Wood Mackenzie Lens calculated global short-run marginal costs (SRMC – operating costs + taxes and royalties) for current production, at the asset level. At a Brent price of US$35/bbl, revenue from 4 million b/d (4%) of global liquids supply does not cover production costs and government share. This rises to 10 million b/d (9%) if prices fall to US$25/bbl.

In the last downturn in 2015/16 virtually no out-of-the money production was shut-in, even at the highest cost wedges. The associated costs are too high. But prices only dipped below US$45/bbl for a year, and below US$35/bbl for one quarter. There is no precedent for the scale of potential shut-ins, if there is a prolonged period of low prices, for today’s asset classes.

The industry’s ability to keep higher-cost barrels flowing will be severely tested. Longer-term, the impact of a lack of spend on maintaining existing production and capital spend to replace declines will take over as the primary driver of supply.

Core producers Saudi Arabia, Russia and the US need to continue drilling wells to maintain production levels. But whereas the Saudi and Russian governments decide their own investment and production levels, the US government does not. Individual company strategies fill that role. Those same companies were challenged financially even before the price fell.

In the short term, companies, governments and other stakeholders are likely to continue producing assets at a loss, as they have in the past, in the hope the price will rebound quickly. But, the current trifecta of oversupply, demand evaporation and global behemoths fighting for market share may require immediate and dramatic action.

Just as companies rush to stem the cash haemorrhage, petro-economies may have to act to avoid steep climbs in budget deficits. Paradoxically, where a high proportion of an asset’s production costs are fixed – think facilities running costs, materials, rent, compliance and so on – the easiest way to reduce unit operating costs is to increase production, if that is an option.

If prices don’t rebound, the taps will inevitably be turned off. Shut-ins will be more substantial than 2015/2016. Given the difficulties and costs associated with restarting mature production, a proportion of this supply may never return.

Where does this leave the upstream service sector?

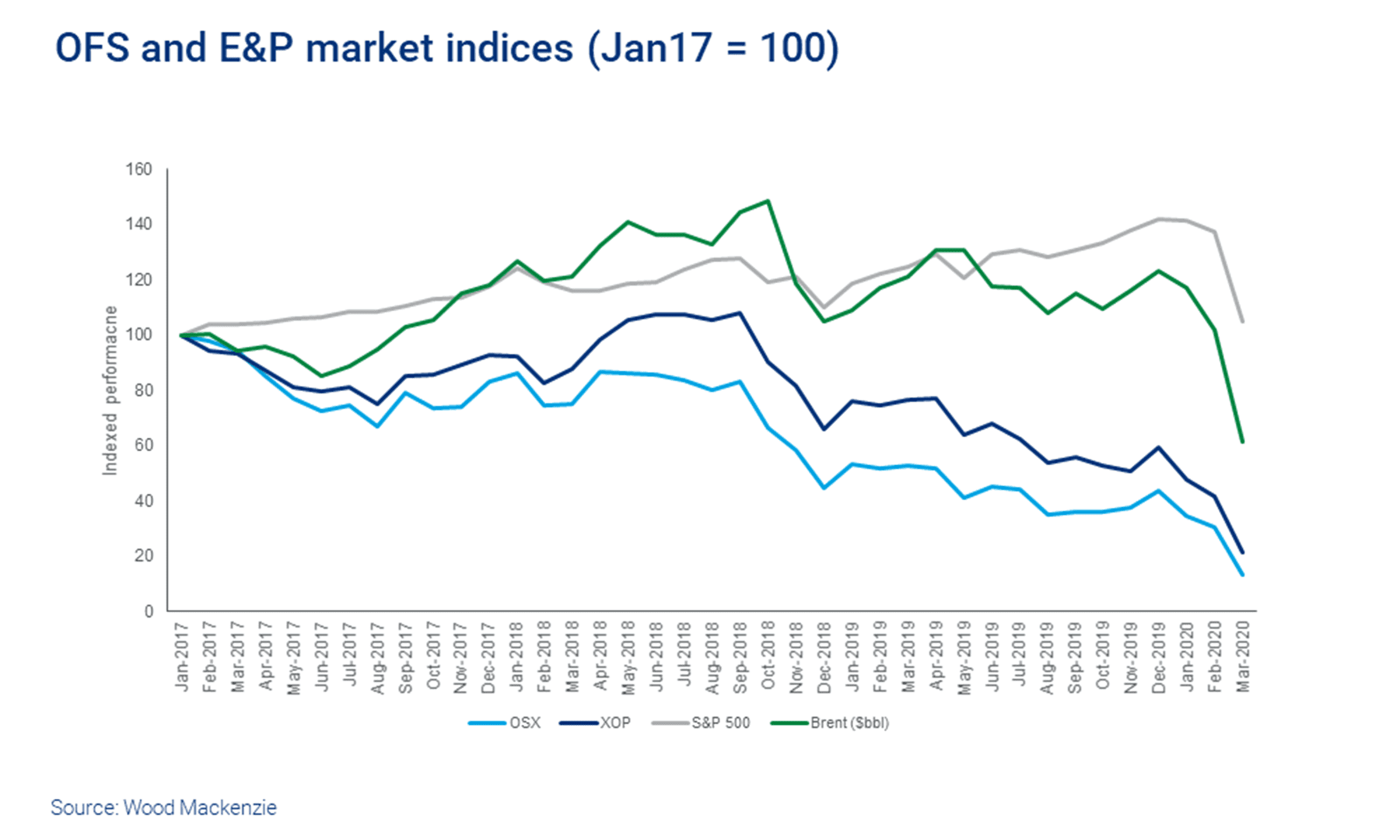

If operators hurt, the supply chain will feel it too – possibly more so. Coming into 2020, the service sector had been struggling with low margins, oversupply and weak investor sentiment. Any optimism regarding 2020 upstream project execution activity, prior to the oil price crash, has been unequivocally reversed.

There are three themes that operators, OFS companies and their investors will have front of mind.

First, equipment and services demand. Even more capital discipline from operators will reduce demand in a big way in 2020. Whether offshore or in the L48, only a handful of major projects are expected to move forward this year.

Second, financial resilience. Stretched balance sheets and low margins were still commonplace for the service sector coming into 2020. Companies had already cut so much, it’s hard to identify further savings without drastic measures. This includes refinancing and the restructuring of business models. Headcount cuts and bankruptcies are inevitable.

And finally, excess capacity. Companies holding onto idle assets “just in case” will quickly think again. We think the prospect of sub-US$40/bbl oil will be enough to force profound change in the sector’s footprint. While there’s undoubted short-term pain associated with this, it could ultimately create a more sustainable business for those that survive the downturn.

Once upstream activity does pick up – whenever that is – the reality of a much smaller and less capable service sector could cause headaches for operators. The elasticity to bounce back quickly may not be there. The strongest service companies will drive collaboration and technology development. A smaller and more efficient industry awaits.

Analysis from Wood Mackenzie’s analysts across the globe, including Mhairidh Evans, Fraser McKay, Tom Ellacott, Robert Morris, Robert Clarke and many more.