By Arthur Deakin – OilNOW

In June of 2022, gas supply from Russia to the European Union fell by nearly two-thirds compared to the previous year. Nord Stream 1, which is responsible for nearly 40% of Russian gas exports to Europe, is currently shut down for a 10-day annual maintenance procedure. Questions are now arising whether Russia will extend that delay to further exert pressure on western Europe, a potential tactic by Putin to ratchet inflation and strain the public’s support for Russian sanctions.

Oil accounted for 10% of Russian GDP in the past five years, while gas represented a mere 2%. That makes a complete shut-down of Russian gas more likely, as indicated by Gazprom’s recent force majeure on the delivery of gas to some European suppliers. Even if the EU’s gas storage levels reach 90% by October 1, and Russian gas supplies are cut off, that stored capacity will only last until April 2023. Hence, a prolonged and cold 2023 winter will cause enormous economic and social consequences for the region, causing a massive rush towards the development of renewable energy and LNG export terminals across the world.

A big beneficiary of this “oil and gas rush” has been Latin America. Americas Market Intelligence (AMI) analysis shows that Peru has increased LNG exports to Europe by over 70% in the first half of 2022. In Mexico, after years of contentious policies aimed at hindering the private sector, AMLO has green-lit several public-private partnerships to develop offshore LNG hubs and export terminals. And perhaps most surprising of all, the U.S is now allowing Venezuelan oil to arrive in European markets.

Nearby in the Americas, Guyana has just unraveled 11 billion barrels of oil equivalent, the largest offshore oil discovery in the past decade. Although the final resource amount will likely be much larger, 20% of the proven reserves are estimated to be associated gas, equal to 13.2 trillion cubic feet (tcf). By those calculations, Guyana now has the third largest gas reserves in the region, behind Venezuela and Argentina.

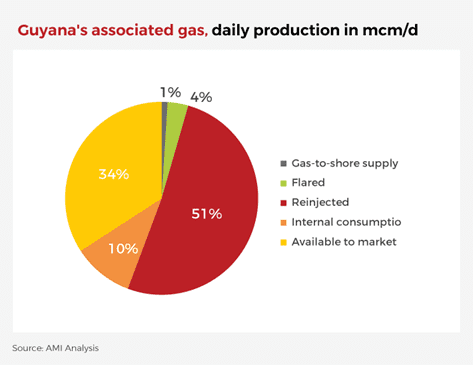

It is still unclear how this newfound resource will be used. Most of it will be reinjected into the underground reservoir to optimize the extraction of oil. A small portion of it will be flared. And another small piece, equivalent to 50 million cubic feet per day, will flow through a 135-mile pipeline to the west bank of the Demerara River. Upon arrival, a Natural Gas Liquid (NGL) plant will create dry gas—used mostly to power a 300MW power plant—as well as other useful liquids such as ethane and propane.

Using Brazil’s most recent gas production data as a relative benchmark (given that they have similar gas reserves and associated gas), AMI estimates that Guyana would have a 34% surplus in gas production after accounting for gas reinjection, flaring, internal consumption, and the gas-to-shore supply. That would mean that Guyana would be able to market 48 million cubic meters of gas per day, enough to replace 11% of Russia’s gas supply to Europe.

For this gas to reach Europe, there are several different alternatives that Guyana can pursue. Given Europe’s urgency and the relatively small size of these exports, an attractive option is New Fortress Energy’s “Fast LNG” solution, an offshore liquefaction and export facility that is developed in 18 to 20 months. In fact, the company has already signed several deals to develop these types of facilities in the Gulf of Mexico. Micro-LNG, or an onshore liquefication and export terminal, are also attractive options—but less so.

Although the current mindset is to “liquify, baby, liquify,” LNG export infrastructure and gas pipelines need to be built transition ready. Massive LNG supply projects, ranging from Qatar to Australia, will come online in the next few years. This means that these LNG projects, which have 30-to-40-year life spans, must also be equipped to transport low carbon fuels such as hydrogen, synthetic methane, and renewable natural gas. The EU, recognizing this need, has allowed gas projects to have a temporary “green taxonomy” if they have plans to switch to low-carbon fuels by 2035. This indicates that the gas infrastructure being developed now needs to match the future needs of the energy transition.

Climate activists are right to point out that gas projects are not the solution for a net-zero economy. Yet, in places like Guyana, where heavy fuel and diesel make up nearly 90% of the generation mix, gas can serve as a “transition” fuel and cut greenhouse gas emissions by up to 50%. This gas-to-shore plant will also reduce electricity costs by roughly 50%, fueling a manufacturing and economic boom that will benefit the local community. It is time for Guyana and its neighbors to capitalize on its abundance of resources, while simultaneously complying with climate targets.

About the Author

Arthur Deakin is Director of AMI’s energy practice, where he helps companies expand into Guyana and the wider Latin American region through market intelligence and analysis. Whether it’s conducting due diligence on local partners, sizing the market, or finding the most attractive risk-adjusted opportunities, AMI has led over 3,000 Latin American market studies since 1993 and has project experience in 20+ jurisdictions in the Americas.