By Fernando Hernandez – OilNOW

To understand Guyana’s meteoric rise as an oil-producing nation, it is necessary to reference critical events that occurred in the U.S.’ Gulf of Mexico (GoM) in 1947 and 1986. These events were crucial to the South American nation rising to prominence on the global stage, regarding its offshore oil production and the discoveries that continue to be made in Guyana’s offshore sector (deepwater, to be specific). And based on the data provided herein, Guyana is on a path to rival the production of OPEC+ member nations and the GoM’s, reference Figure 3 and 4, respectively. Thus, it is not surprising that Guyana continues to garner global interest and awe, all while inspiring other nations in the South American and Caribbean region, such as Suriname, to further their offshore pursuits. Notably, this article will outline the rich history—and catalysts—that connects two countries on different continents via the U.S. and Guyana, and how the latter has evolved to forge its own distinct path in such an accelerated timeframe.

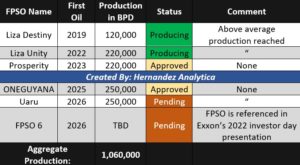

Said events were critical to Guyana making the Liza discovery at a depth of 5,000 ft. in 2015. To be clear, other occurrences and developments transpired before Guyana became a prolific producer: within and outside of the GoM. Following the Liza discovery, Guyana would have its first-ever producing FPSO by 2019, in record time: less than five years, as a result of the Liza Destiny FPSO. ExxonMobil’s (Exxon) offshore successes in the Gulf of Mexico played a key role in the South American nation making a quantum leap to become a deepwater producer. This is bolstered by Exxon, the U.S. super major—making an additional commitment to expand its footprint in Guyana, as highlighted in Figure 2.

That said, the first event that would be a catalyst for Guyana’s rise occurred in 1947 when the first out-of-sight well was developed (at a depth of 20 ft.) by Kerr McGee in the GoM. This spurred further offshore exploration and production (E&P) work in the U.S., leading to additional discoveries in deeper waters. The second event comes in 1986 when the first well that surpassed the 5,000 ft. marker was drilled and discovered; this would become Shell’s Mensa field, which would reach first production in 1995. Comparatively, Guyana reached this depth 20 years later with the Liza discovery.

Guyana’s Importance in Expanding the Golden Deepwater Triangle

In a piece for Forbes written in 2020, the author began accounting for Guyana’s prominence in the golden deepwater triangle, back when Guyana only had one oil producing platform. For context, there are only three regions globally with deepwater plays, composed of the GoM, West Africa, and Eastern South America (historically through Brazil), which Guyana continues to contribute to and expand on. Moreover, Exxon has a presence in all three parts of the triangle; however, Exxon’s interest in the GoM has dwindled, and it has offloaded GoM assets, while reducing its deepwater operations to just one platform. In addition to the GoM, there are reports that Exxon is also looking to tactfully withdraw its Equatorial Guinea in West Africa.

To remind you, Shell left Guyana due to geological doubts. Exxon subsequently turned its attention to Guyana—in conjunction with CNOOC, and HESS—to fill the void, and gained substantial financial rewards while simultaneously boosting Guyana’s GDP on an upward trajectory. Today, Guyana has demonstrated that it is no longer an uncertain experiment in the golden deepwater triangle but has instead solidified its position as part of the triangle. Moreover, over the course of three years, the South American country remarkably boosted its production at an average pace of around 120,000 BPD per year, bringing its output to roughly 160,000 BPD. When accounting for production from present and future FPSOs—as listed in Figure 2, this illustrates that Guyana is expected to hit the one million BPD milestone in 2026 (seven years from first oil from the inaugural Liza Destiny FPSO).

Guyana’s Race to Reach 1-Million BPD

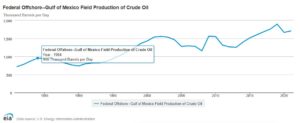

Once more, we find Guyana on the cusp of achieving a significant achievement. How so? As can be seen in Figure 3, it took the GoM 38 years, from 1947 (when the Kerr McGee development began) until 1985, to reach 956,000 BPD. Guyana, on the other hand, is positioned to reach 1 million BPD in seven years. Additionally, the U.S. needed 72 years to achieve a record high of 1.9 million BPD in 2019.

It is possible that Guyana will equal, or perhaps surpass the GoM’s record high as we enter the ensuing decade should further projects be approved in Guyana (based on its continued drilling success). Additionally, this is contingent upon the wells located there maintaining their ideal levels of production. If Guyana manages to surpass 1.9 million BPD in such a short amount of time, it will be an unparalleled accomplishment, all while firmly placing itself alongside OPEC+ members. However, the fact that Guyana can potentially produce somewhere within the range of 1 to 1.9 million BPD is significant in and of itself.

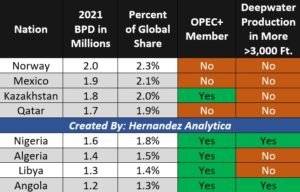

Figure 4 shows that five OPEC+ member nations generate more than 1 million BPD, in 2021, with only two having deepwater producing assets in more than 3,000 ft. Because of this, it is not surprising that Saudi Arabia, a de facto head of OPEC+, has signaled its interest in strengthening its connections to Guyana. The energy equation in Latin America and the Caribbean, and maybe the world, can be pronouncedly altered by the South American nation as it strengthens its position. It is important to note that the output figures presented in Figures 3 and 4 are likely to change throughout the course of the subsequent years; despite this, they serve as a reference benchmark for Guyana.

Guyana’s Low Carbon and Oil Pursuits

It is essential to emphasize that Guyana has designed its Low-Carbon Development Strategy 2030, illustrating how the country can pursue oil production while concentrating on placing such investments on its energy transition pathway. This is similar to Norway, which produced 2.0 million BPD in 2021 yet managed to become the number one Electric Vehicle (EV) nation (per capita) in the world. Guyana is only getting started on the process of building up its EV infrastructure. Despite this, Norway’s expertise might be helpful to the South American nation. In conclusion, as we get closer to the year 2030, it will be very important to keep a close check not just on the country’s low carbon and energy transition goals, but also on its oil production. At the time of this writing, one thing is abundantly clear: Guyana has given the oil world a myriad of reasons to take attention.

About the Author

Fernando C. Hernandez is an accomplished commercial and technology specialist in energy and the principal at Hernandez Analytica. The First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, appointed Hernandez as a business ambassador (GlobalScot) for Scotland in Americas’ energy sector. He has more than 15 years of industry experience, and his tri-lingual fluency has enabled the execution of challenging projects in multiple continents. Hernandez collaborates with Scottish Development International on diverse energy projects and has two additional appointments: Technology Mentor for the Net Zero Technology Centre (UK), and Chairman at the Marine Technology Society (US). Additionally, he has a history of providing industry contributions to the Mexican Institute of Petroleum, Scottish Enterprise, American Petroleum Institute, US Coast Guard, US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, and Pipeline Research Council International.