The Council on Foreign Relations

Written by Amelia Cheatham and Rocio Cara Labrado

Venezuela’s descent into economic and political chaos in recent years is a cautionary tale of the dangerous influence that resource wealth can have on developing countries.

Venezuela, home to the world’s largest oil reserves, is a case study in the perils of petrostatehood. Since it was discovered in the country in the 1920s, oil has taken Venezuela on an exhilarating but dangerous boom-and-bust ride that offers lessons for other resource-rich states. Decades of poor governance have driven what was once one of Latin America’s most prosperous countries to economic and political ruin. If Venezuela is able to emerge from its tailspin, experts say that the government must establish mechanisms that will encourage a productive investment of the country’s vast oil revenues.

What is a petrostate?

Petrostate is an informal term used to describe a country with several interrelated attributes:

- government income is deeply reliant on the export of oil and natural gas,

- economic and political power are highly concentrated in an elite minority, and

- political institutions are weak and unaccountable, and corruption is widespread.

Countries often described as petrostates include Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Ecuador, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Libya, Mexico, Nigeria, Oman, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.

What’s behind the petrostate paradigm?

Petrostates are thought to be vulnerable to what economists call Dutch disease, a term coined during the 1970s after the Netherlands discovered natural gas in the North Sea.

In an afflicted country, a resource boom attracts large inflows of foreign capital, which leads to an appreciation of the local currency and a boost for imports that are now comparatively cheaper. This sucks labor and capital away from other sectors of the economy, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which economists say are more important for growth and competitiveness. As these labor-intensive export industries flag, unemployment could rise, and the country could develop an unhealthy dependence on the export of natural resources. In extreme cases, a petrostate forgoes local oil production and instead derives most of its oil wealth through high taxes on foreign drillers. Petrostate economies are then left highly vulnerable to unpredictable swings in global energy prices and capital flight.

The so-called resource curse also takes a toll on governance. Since petrostates depend more on export income and less on taxes, there are often weak ties between the government and its citizens. Timing of the resource boom can exacerbate the problem. “Most petrostates became dependent on petroleum while, or immediately after, they were establishing a democracy, state institutions, an independent civil service and private sector, and rule of law,” says Terry Karl, a professor of political science at Stanford University and author of The Paradox of Plenty, a seminal book on the dynamics of petrostates. Leaders can use the country’s resource wealth to repress or co-opt political opposition.

How does Venezuela fit the category?

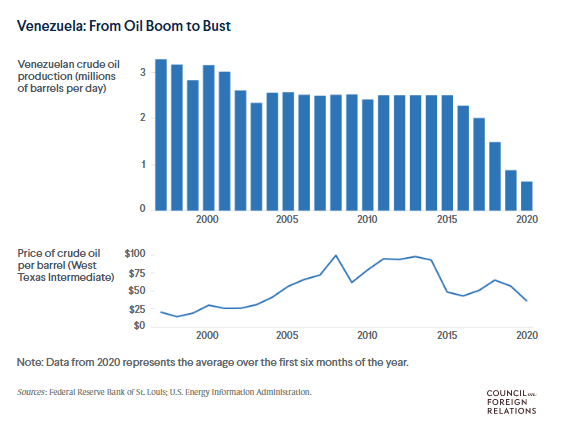

Venezuela is the archetype of a failed petrostate, experts say. Oil continues to play the dominant role in the country’s fortunes more than a century after it was discovered there. Oil prices plunged from more than $100 per barrel in 2014 to under $30 per barrel in early 2016, sucking Venezuela into an economic and political spiral. Conditions have only worsened since then.

A number of grim indicators tell the story:

Oil dependence. Oil sales make up 99 percent of export earnings and roughly one-quarter of gross domestic product (GDP).

Falling production. Starved of adequate investment and maintenance, oil output has declined to its lowest level in decades.

Spiraling economy. GDP shrank by roughly two-thirds [PDF] between 2014 and 2019, and experts forecast that, with plummeting demand for oil amid the coronavirus pandemic, it would decline by roughly another 30 percent in 2020.

Soaring debt. Venezuela has an estimated debt burden of $150 billion or higher, more than double the estimated size of its economy.

Hyperinflation. Annual inflation is running at 6,500 percent.

Growing autocracy. President Nicolas Maduro and his allies have violated basic tenets of democracy to maintain power.

These issues—coupled with international sanctions and the coronavirus pandemic—have fueled a devastating humanitarian crisis, with severe shortages of basic goods such as food, drinking water, gasoline, and medical supplies. According to a recent survey, 96 percent of Venezuelans live in poverty, the highest proportion in Latin America.

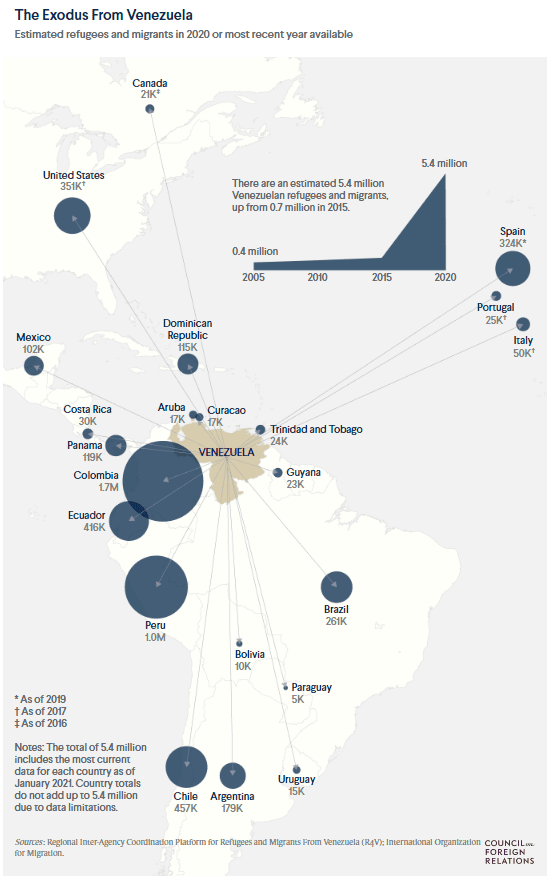

Since 2015, more than five million people have fled to neighboring countries and beyond. However, over one hundred thousand Venezuelan migrants have returned home since the coronavirus pandemic began, often after losing their jobs in other Latin American countries.

How did Venezuela get here?

A number of economic and political milestones mark Venezuela’s path as a petrostate.

Discovering oil. In 1922, Royal Dutch Shell geologists at La Rosa, a field in the Maracaibo Basin, struck oil, which blew out at what was then an extraordinary rate of one hundred thousand barrels per day. In a matter of years, more than one hundred foreign companies were producing oil, backed by dictator General Juan Vicente Gomez (1908–1935). Annual production exploded during the 1920s, from just over a million barrels to 137 million, making Venezuela second only to the United States in total output by 1929. By the time Gomez died in 1935, Dutch disease had settled in: the Venezuelan bolivar had ballooned, and oil shoved aside other sectors to account for 90 percent of exports.

Reclaiming oil rents. By the 1930s, just three foreign companies—Royal Dutch Shell, Gulf, and Standard Oil—controlled 98 percent of the Venezuelan oil market. Gomez’s successors sought to reform the oil sector to funnel funds into government coffers. The Hydrocarbons Law of 1943 was the first step in that direction, requiring foreign companies to give half of their oil profits to the state. Within five years, the government’s income had increased six-fold.

Punto Fijo pact. In 1958, after a succession of military dictatorships, Venezuela elected its first stable democratic government. That year, Venezuela’s three major political parties signed the Punto Fijo pact, which guaranteed that state jobs and, notably, oil rents would be parceled out to the three parties in proportion to voting results. While the pact sought to guard against dictatorship and usher in democratic stability, it ensured that oil profits would be concentrated in the state.

OPEC. Venezuela joined Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia as a founding member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960. Through the cartel, which would later include Qatar, Indonesia, Libya, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Nigeria, Ecuador, Gabon, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of Congo, the world’s largest producers coordinated prices and gave states more control over their national industries. That same year, Venezuela established its first state oil company and increased oil companies’ income tax to 65 percent of profits.

The 1970s boom. In 1973, a five-month OPEC embargo on countries backing Israel in the Yom Kippur War quadrupled oil prices and made Venezuela the country with the highest per-capita income in Latin America. Over two years, the windfall added $10 billion to state coffers, giving way to rampant graft and mismanagement. Analysts estimate that as much as $100 billion was embezzled between 1972 and 1997 alone.

PDVSA. In 1976, amid the oil boom, President Carlos Andres Perez nationalized the oil industry, creating state-owned Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) to oversee all exploring, producing, refining, and exporting of oil. Perez allowed PDVSA to partner with foreign oil companies as long as it held 60 percent equity in joint ventures and, critically, structured the company to run as a business with minimal government regulation.

The 1980s oil glut. As global oil prices plummeted in the 1980s, Venezuela’s economy contracted and inflation soared; at the same time, it accrued massive foreign debt by purchasing foreign refineries, such as Citgo in the United States. In 1989, Perez—reelected months earlier —launched a fiscal austerity package as part of a financial bailout by the International Monetary Fund. The measures provoked deadly riots. In 1992, Hugo Chavez, a military officer, launched a failed coup and rose to national fame.

Chavez’s Bolivarian revolution. Chavez was elected president in 1998 on a socialist platform, pledging to use Venezuela’s vast oil wealth to reduce poverty and inequality. While his costly “Bolivarian missions” expanded social services and cut poverty by 20 percent, he also took several steps that precipitated a long and steady decline in the country’s oil production, which peaked in the late 1990s and early 2000s. His decision to fire thousands of experienced PDVSA workers who had taken part in an industry strike in 2002–2003 gutted the company of important technical expertise. Beginning in 2005, Chavez provided subsidized oil to several countries in the region, including Cuba, through an alliance known as Petrocaribe. Over the course of Chavez’s presidency, which lasted until 2013, strategic petroleum reserves dwindled and government debt more than doubled.

Chavez also harnessed his popularity among the working class to expand the powers of the presidency and edged the country toward authoritarianism: he ended term limits, effectively took control of the Supreme Court, harassed the press and closed independent outlets, and nationalized hundreds of private businesses and foreign-owned assets, such as oil projects run by ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips. The reforms paved the way for Maduro to establish a dictatorship years after Chavez’s death.

Descent into dictatorship. In mid-2014, global oil prices tumbled, and Venezuela’s economy went into free fall. As unrest brewed, Maduro consolidated power through political repression, censorship, and electoral manipulation. In 2018, he secured reelection in a race widely condemned as unfair and undemocratic. Nearly sixty countries, including the United States, subsequently recognized opposition figure Juan Guaido, head of the National Assembly, as Venezuela’s interim leader.

In recent years, Washington has escalated sanctions against Caracas, which have curtailed the Maduro government’s income. Still, Venezuela has retained oil-trading partners, and analysts say that support from China, Cuba, Iran, Russia, and Turkey is keeping the Maduro regime afloat.

In January 2021, Maduro and his allies took leadership of what was the last opposition-controlled power center in the government, the National Assembly, after claiming victory in legislative elections. The opposition, including Guaido, boycotted the vote, alleging that it was fraudulent, a charge supported by the United States and other foreign governments. Some analysts predict that, with the legislature now under his sway, Maduro will step up his repressive tactics.

Is there a path away from the oil curse?

A country that discovers a resource after it has formed robust democratic institutions is usually better able to avoid the resource curse, analysts say. For example, strong institutions in Norway have helped the country enjoy steady economic growth since the 1960s, when vast oil reserves were discovered in the North Sea, Karl writes in her book. In 2019, the petroleum sector accounted for close to 14 percent of Norway’s GDP. Strong democracies with an independent press and judiciary help curtail classic petrostate problems by holding government and energy companies to account.

If a country strikes oil or another resource before it develops its state infrastructure, the curse is much harder to avoid. However, there are remedial measures that low-income and developing countries can try, provided they are willing. For instance, a government’s overarching objective should be to use the oil earnings in a responsible manner “to finance outlays on public goods that serve as the platform for private investment and long-term growth,” says Columbia University’s Jeffrey Sachs, an expert on economic development. This can be done financially, with broad-based investing in international assets, or physically, by building infrastructure and educating workers. Transparency is essential in all of this, Sachs says.

Many countries with vast resource wealth, such as Norway and Saudi Arabia, have established sovereign wealth funds (SWF) to manage their investments. Globally, SWFs manage about $9 trillion worth of assets.

Analysts anticipate that a global shift from fossil fuel energy to renewables such as solar and wind will force petrostates to diversify their economies. Nearly two hundred countries, including Venezuela, have joined the Paris Agreement, a binding treaty that requires states to make specific commitments to mitigate climate change.

Economic diversification will be an especially difficult climb for Venezuela given the scale of its economic and political collapse over the last several years. The country would likely need to revitalize its oil sector before it could cultivate and develop other important industries. But this would take enormous investment, which analysts say would be hard to come by given Venezuela’s unstable political environment, trends in oil demand, and rising concerns about climate change.

About the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations, founded in 1921, is a United States nonprofit think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international affairs. It is headquartered in New York City, with an additional office in Washington, D.C.