By Arthur Deakin – OilNOW

For those that follow Guyana, the success rate and speed in which its oil resource has been developed is unprecedented. 11% of all conventional oil found in the world since 2015 has been off the coast of Georgetown. In fact, the discoveries have been so impressive and consistent in the Guyana-Suriname basin that it has created a numbing effect—operators and investors almost expect new discoveries to be made on a monthly basis.

But rather than praise the remarkable findings and projections, as a consultancy that works to ensure successful client engagements in Latin America, AMI wanted to briefly touch upon some of the risks and opportunities faced by investors in Guyana. This research gave us a clear view of the Guyanese sectors that are poised to do the best in the next 5 to 20 years.

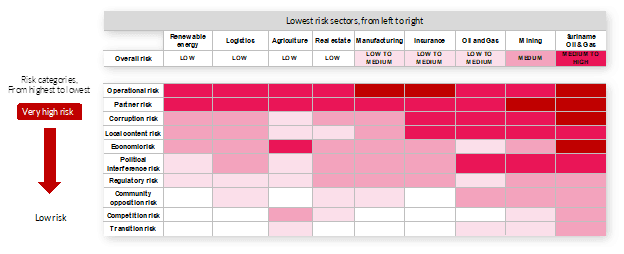

Figure 1: AMI risk analysis of Guyana’s main sectors

As a means of comparison to another frontier market in the region, AMI also applied its risk analysis to Suriname’s oil and gas industry. Suriname’s oil and gas sector came out as “medium to high risk” because of its distressed economic situation, its relatively unproven oil discoveries, its unclear local content policies and a history of corruption and mismanagement by the government.

As we’ve seen in numerous other frontier oil markets, and even in more developed jurisdictions such as Brazil’s pre-salt fields, the CapEx necessary for exploration often reaches the hundreds of millions of dollars before a significant discovery is made. That was the case in Guyana before 2015, which led to the sale of Shell’s participation in the Stabroek block. In many other cases, no discoveries are made after decades of drilling, forcing companies to go home with billion-dollar losses and nothing to show. Suriname has made some discoveries in Block 58 and 52, but it is still a relatively green and risky jurisdiction.

When compared to Suriname’s oil and gas industry, all of Guyana’s sectors scored well, with mining being the only one falling in the “medium risk” category. Guyana’s good performance is a result of its proven oil and gas discoveries, its projected economic growth, its relatively stable regulatory frameworks, and its limited local community opposition. Sectors such as renewable energy, agriculture, logistics and real-estate, were all deemed as “low risk,” while insurance, manufacturing and oil & gas fell in the “low to medium risk” categories.

Although the oil and gas sector will bring in much larger revenues than the renewable sector in Guyana, it is also a much bigger target for political and local interference. There is no local capacity to match the scale of its development and the government is already signaling stricter production sharing agreements (PSA), a worrisome sign for investors. On the contrary, renewable energy has both the government and public’s backing, making it Guyana’s greatest opportunity relative to risk.

Currently, the government is actively looking for renewable energy developers and investors to satisfy the three-fold growth in energy demand expected by 2026. Some of that power will be satisfied with the 300MW gas-to-power project in Wales, but that project will need to be complemented by waste-to-energy solutions, solar panels in the hinterland, medium sized hydro projects and wind power coming off the Atlantic.

The renewable energy sector also includes opportunities related to the much-needed decentralization of the grid, such as battery storage and the development of micogrids, two important tools in electrifying rural areas, preventing blackouts, and providing firm power to offset intermittency. Guyana could also use its 16 trillion cubic feet of gas to produce blue hydrogen, which uses natural gas and carbon capture technology to produce the clean fuel. The production would be possible if the public and private sector developed an eco-industrial park connected to the proposed gas-to-energy plant, allowing Guyana to clean its grid while promoting industrialization.

Despite the attractiveness of the renewable sector, investors should not be oblivious to the challenges posed by these projects. Sometimes, bureaucratic red tape, inadequate grid infrastructure and land-disputes with local communities delay the approval of said projects. To mitigate these risks, the government needs to create the appropriate subsidies and the right framework to attract large-scale investment in the sector.

More broadly, when looking at AMI’s 10 risk categories, the analysis suggests that operational risk, followed closely by partner risk, are the two biggest concerns for companies and investors alike. Operational risk considers whether there is enough local capacity and infrastructure for the development of projects. And the second largest risk, Partner risk, measures the likelihood that a local partner successfully delivering on their obligations and commitments.

In both Guyana and Suriname, there is still a major gap between local labor capacity and expected demand. The Ali administration has emphasized this point repetitively by saying that Guyana is near full employment even though only two of potentially 10 FPSOs are currently operational. Energy investors and operators both agree that the biggest developmental challenge in Guyana is the lack of human capital.

This does not mean that Guyana lacks qualified companies or that its people can’t rise to the challenge. On the contrary, after attending the Guyana Energy Conference two weeks ago, the Guyanese people reemphasized that they are extremely eager and willing to participate in this economic transformation. Sometimes, all they need, is a foreign company to take a leap and use their services. Comprehensive due diligence, and good connections, will help foreign companies find the right partners and limit reputational hiccups. Better education, starting with investments at the primary level, as well as a looser immigration policy, are also vital to develop the local capacity.

The relatively low level of Guyana’s oil and gas “transition risk,” which measures how the sector will be impacted in a net-zero world, might appear surprising. But its score is explained by the country’s low breakeven costs, its attractive regulatory framework, its high-quality crude, and its impressive drilling success rates.

Despite these positive attributes, there is still great value in transforming Guyana into a new type of oil & gas producer: one in which fossil fuel production is mixed with carbon capture technologies, cleaner power generation, and nature-based solutions. This will allow for Guyana’s energy sector to be preferred over other dirtier, less profitable, and riskier jurisdictions. To ensure this is done quickly, and is feasible, the government must develop carbon credits and implement a carbon price.

Guyana is off to a decent start with the early creation of its sovereign wealth fund and local content policy, but the government should also work with the private sector to develop better infrastructure, create a more robust healthcare system, and greatly improve its education. This is going to require large investments that are accelerated via free trade zones, tax credits, subsidies, and government-backed loans to qualifying companies and investors.

Although frontier countries should have the right to extract their resources, especially if they can substantially improve the living standards of its people, they must limit their carbon footprint and ensure that revenues are spent transparently. Guyana seems to be heading down the right path and is well positioned to transform its economy and the wider region. However, it must ensure that it does not get lost in the headlights of this newfound popularity.

About the Author

Arthur Deakin is co-director of AMI’s energy practice, where he oversees projects in solar, wind, biomass and hydrogen power, as well as energy storage, oil & gas and electric vehicles. Arthur has led close to 50 Latin American energy market studies since 2017 and has project experience in over 20 jurisdictions in the Americas. He has also written and published over 20 articles related to the energy sector.