(Hart Energy) Mark Twain would appreciate irony in the Eagle Ford Shale, where rumors of the play’s impending exhaustion are greatly exaggerated.

The Eagle Ford has produced 2.5 billion barrels (Bbbl) of oil and will generate another 2.1 Bbbl, according to Allen Gilmer, CEO of DrillingInfo, the Austin, Texas-based Big Data repository of all things oil and gas. The play has also produced 10 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas and is on track to produce another 5 Tcf to 6 Tcf.

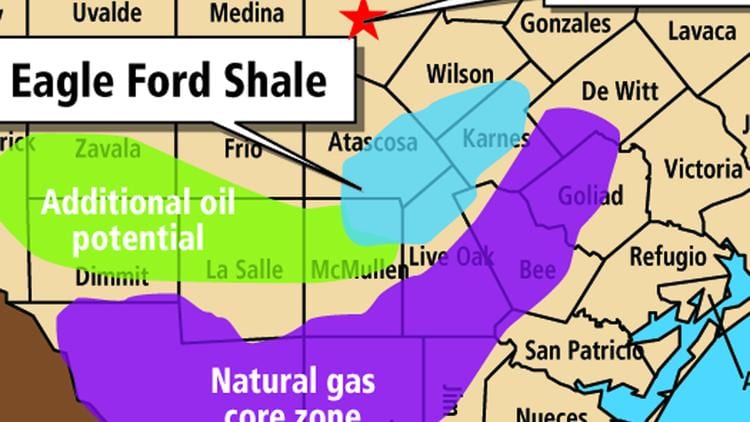

DrillingInfo compiles datapoints on rock quality, drilling parameters and completion techniques. Internally, the company correlates well metric variables to rock quality in an attempt to determine which aspects of rock quality drive are producible. The company has classified 10 grades of rock across the play, which stretches from the Mexican border east and north to the area around Bryan/College Station, Texas.

“The reason we did this—and it’s not perfect; there is no perfect answer to any of these things—but this gives us a basis to compare efforts among operators and the ability to create a standard play map and to do comparative operator analysis,” Gilmer said.

The industry has drilled up to 90% of the best grade rock, but only about 30% of the largest tranche of mid-quality rock. Median peak rates for the best rock average 922 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d) across 2,000 wells vs. 367 boe/d in mid-grade rock across more than 5,500 wells.

The highest quality rock has about 230 locations remaining vs. more than 13,000 locations for mid-grade rock. Depending on future well spacing, the Eagle Ford is either a third to a sixth developed in terms of well count.

“I always felt that the recoverable reserves in the Eagle Ford were going to be on the order of 20 billion barrels of oil,” Gilmer said. “It could be higher. Frankly, 20 billion is not a bad number, which is equivalent to what Texas A&M says. It’s about twice as high as what UT (University of Texas) and the USGS (United States Geologic Survey) say.”

Grading incorporates analytic measures ranging from peak rates per day to cumulative oil production over any chosen time period. Grading incorporates wellbore geometrics that examines, for example, lateral tortuosity, whether laterals are toe up or down. How well did a lateral stay within the producing zone? What azimuths are E&Ps using for lateral direction? This data is correlated with the quality of rock, downhole temperatures, and closeness to faults among other variables.

“There are literally hundreds of relationships with production,” Gilmer said. “As you can see, most of these relationships are pretty complicated. They’re pretty nonlinear. But these are all inputs into how you address how you’re going to model the play because, if you really think about it, it’s just a big non-linear multi-grid problem.”

At the end of the day, the gas-oil ratio (GOR) is a major driver, as is production normalized for horizontal length. Other parameters discussed in public presentation involve proppant volume in producing intervals. But, parameters that are less discussed publicly include resistivity, shale volume thickness, and density porosities. The industry tends to normalize production based on lateral length and proppant density, which Gilmer says is a good starting point.

“But, what you really want to do is normalize the rocks,” he said.

Gilmer presented cumulative production data from 100 wells in McMullen County. When that data was normalized for engineering, it revealed that E&Ps were overspending up to $1.5 million per well in costs that provided no net positive contribution to return on investment.

“This was an area where I could have really cut back and been able to save money because it was not contributing to getting me more hydrocarbon,” Gilmer said.

In contrast, Gilmer noted other areas were under-optimized and E&Ps could have produced more hydrocarbons by spending a little more on well completion techniques. At the end of the day, grading confirms that one company’s trash can very well become another company’s treasure.

“That’s what still makes this an interesting play,” Gilmer said. “It’s a place where you can go buy acreage and make it much better if you’re buying it from people who didn’t really know what they were doing. It’s also a place where you can go buy acreage from people that are doing very well and not be able to perform once you have bought it.

Gilmer reviewed several pairs of E&Ps and their relative success vs. one another. EOG Resources Inc. (NYSE: EOG), for example, performs highly on lower grades of rock compared to the median among peers in similar rock grades, but not as well in the best rock grades when contrasted with the highest performing peers.

On the other hand, ConocoPhillips Co. (NYSE: COP) performs above the mean vs. peers across all grades of rock. ConocoPhillips employs an aggressive choke strategy and the company’s well production tends to be better over time vs. peers when using cumulative oil as a yardstick.

Gilmer presented an example of two companies operating side by side in the same geography, and in the same grade of rock. Those companies displayed significant differences in cumulative oil production. Gilmer also spotlighted a recent transaction where the purchasing party performed below the levels of the selling party.

“When you’re buying assets, you better make sure that you know what you’re buying with regards to being able to replicate the result,” he said.

When it comes to in-house analysis, DrillingInfo has a preference for staggering wells on top of each other over time for each individual E&Ps.

“We like these kinds of charts because these are a great way of seeing that people have changed what they’re doing. If you see a big inflection point and a company gets better, that means they changed the methodology of what they were doing. You can go in and look at the details to see exactly what they did.”

Actually, the industry, as a whole, has gotten better. Average Eagle Ford IPs grew from 250 boe/d a decade ago to 510 boe/d in the 2013 to 2015 era. It is currently above 700 boe/d.

“What this does is make nearly the whole play economic,” Gilmer said. He noted 80% of the play can produce IRRs above 20% with the hottest parts of the Eagle Ford generating upwards of 100% IRRs.

Gilmer did a quick review of other formational targets. The best parts of the Austin Chalk overlie the best parts of the Eagle Ford. Elsewhere, the underlying Buda has produced 700 boe/d in a handful of sweet spots. Other formations varied in production and geographical extent though several are equivalent in yield to the Eagle Ford at a similar stage of development.

Gilmer itemized recent trends. For example, Eagle Ford E&Ps are beginning to source more of their own chemicals and fluids directly rather than outsourcing to service companies.

A second trend involves enhanced recovery, which is currently focused on reinjection of natural gas for pressure maintenance. Enhanced recovery is early in evolution and the industry is studying techniques such as ethane injection since ethane is currently low cost because of oversupply.

Current geologic inquiries involve extensive fracture mapping. In terms of completion technique, the industry is beginning to incorporate greater use of diverters, which is opening possibilities for recovering stranded oil via infill drilling.

“This concept of being able to recharge these wells with ethane or hydrocarbons, and then divert production from a recompletion or completion point of view is really important,” he said.

Unlike Mark Twain’s observation that everyone talks about the weather, but no one does anything about it, Eagle Ford E&Ps are, in fact, figuring out how to squeeze a little more oil and gas from a play that’s just now hitting its geologic stride.