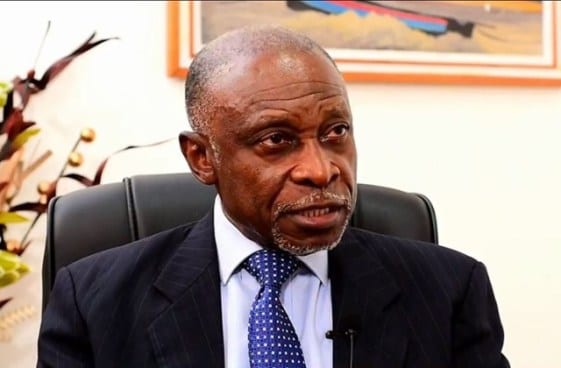

Some stakeholders in Guyana have argued that the new oil producing South American country has at its disposal, the choice to opt-out of obligations under the Caribbean Community’s (CARICOM) Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas (RTC) so as to ensure the spirit and intention of its Local Content Act are protected. But government’s Advisor on Borders, Carl Greenidge warned that doing so would be unwise.

Greenidge’s word of caution follows comments put forward last week by Member of Parliament Sanjeev Datadin, that if Guyana so chooses, it can issue a reservation to opt-out of any treaty obligation as a means of ensuring Guyanese companies and individuals are not marginalised by competing CARICOM nationals in the oil and gas sector.

Similar sentiments were also shared by President of the Georgetown Chamber of Commerce and Industry (GCCI), Timothy Tucker who was particularly critical of the CARICOM Private Sector Organization (CPSO) leadership for challenging the legality of Guyana’s Local Content legislation as regards its compliance with the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME). Tucker is of the fervent view that Guyanese ought to be given a chance to build their capacities and allowed first consideration for opportunities to benefit from their oil resources.

On Tuesday via his Facebook profile, Tucker even laid at Greenidge’s feet, some of the blame for where Guyana finds itself, in a fight to preserve the powers and rights enshrined in its Local Content Act.

Tucker contended that Guyanese have suffered from the “most discrimination, ill-treatment, rejection of goods and services by CARICOM member states.”

He recalled that back in 2018, GCCI had told the then government not to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Energy Cooperation with Trinidad until they removed all non-tariff barriers to trade with Guyana. He said this advice was ignored on the basis that Trinidad had loaned Guyana US$96 million back in the 1980s. That matter aside, the GCCI President articulated that the issue at hand goes beyond the Local Content law.

He said, “It is about how Guyana, Guyanese citizens, and Guyanese businesses have been treated within CARICOM and especially by Trinidad. It is also how Trinidad as a country has manipulated CARICOM and taken advantage of the entire region and nothing can be done about it. It is how the business community sits in the room and sees multiple Guyanese Governments try to obey the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas while multiple CARICOM member states break the rules set out by the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED), and disregard decisions of CARICOM when it goes against the interest of their country’s business community…”

While Greenidge told OilNOW that he understands the emotions fuelling such positions, he categorically maintained that the government and the country by extension, has a duty to be strategic in its relations. In so doing, he asserts that there are some fundamental principles in international law that citizens must begin to grasp.

The economist explained that non-discrimination has been a key principle underlying the negotiations on liberalisation of the international trading system since the end of World War II and the start of the Uruguay Round in 1982 in particular. Greenidge in a statement shared with OilNOW said non-discrimination is captured in two rules known as the Most Favoured Nation treatment (MFN) and the National Treatment obligation. Greenidge explained that the MFN obligation, the subject of the first General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Article, prohibits a country from discriminating between other countries. Where special privileges are granted, he said those have to be extended to all other trading partners. Ironically, given the present context, Greenidge said that the main exception to this rule is a Common Market – such as the CARICOM Single Market and Economy. He said there is absolutely no reference to petroleum, which incidentally has no significance in economics beyond being a commodity.

Greenidge said too that there is neither an exception based on a particular definition of local content nor free movement. He said the consistency simply turns on whether ‘Chaguaramas’ permits Caribbean nationals/firms to be treated differently from Guyanese.

To set the record straight on this front, the former Foreign Affairs Minister said Article 7, Article 31 (2a & 2b), and Article 37 of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas in particular, do not permit it, except in clearly defined terms.

Greenidge said, “Opt-outs may be sought and secured during negotiations but not 50 or 5 years after Treaties have been signed and invariably require the consent of the other parties (Article 237 of the RTC states: Reservations may be entered to this Treaty with the consent of the signatory States).”

Greenidge said Guyana is therefore not in a position to ignore the rule on grounds that it has “either now thought up a justification or has just begun the production of petroleum.”

Greenidge added, “…That a debate of such import could so quickly reflect heightened ill-will, shows how easily public debate in Guyana, whether in politics or business, can quickly degenerate into personal attacks and abuse. Whilst the Guyana government has not been party to these contentious exchanges, one of its prominent and new Members of Parliament (MPs) has been. Recently, President Irfaan Ali offered a comment to the effect that no Head of State has complained of the alleged breach of the Treaty.”

The economist sought to remind both Datadin and Tucker that after the United States and Canada, the Caribbean is Guyana’s most important export market. He opined that being closed out of the latter market will, no doubt, adversely affect the long-term prospects of Guyana’s key industries and frustrate any effort to diversify out of petroleum products.

But apart from the perspectives of trade relations and what the RTC permits, Greenidge said there is an even greater dimension of the argument that perhaps has escaped the attention of Datadin and Tucker. He said this aspect pertains to Venezuela.

The Advisor on Borders reminded that Guyana’s complaint before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against the Venezuelan government is based on a number of factors, among the most important of which, is Venezuela’s breach of one fundamental legal principle—A State cannot sign a treaty, benefit from the implementation of its provisions for over 63 years then, when convenient, simply unilaterally declare the treaty null and void.

Greenidge explained that the “sanctity of treaties” is enshrined and well protected in Article 26 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT). Thus, either both parties have to agree on invalidity, or a Court or other Tribunal would have to do so. Since Guyana will not agree to invalidate the Paris Arbitration Award, he said Venezuela would need to seek from a competent international tribunal or authority a declaration to that effect. It has refused to do so.

Greenidge further explained that a second concern about Venezuela’s position turns on a matter not yet before an international Court. In this regard, he noted that Venezuela’s proclamation of Decrees (referred to as Leonie Decree of 10th January 1968; 1781 of May 27, 2015; 1859 of 2015; 4415 of Jan 2021, inter alia), in its local legislation purports to confer maritime rights, to which it would not be entitled under international law. Greenidge said the reason for this is hinged on a cardinal principle of international law, that states’ [ex post facto] domestic legislation cannot override obligations entered into under the international treaties a country signs. In fact, Greenidge highlighted that Article 27 of the VCLT states that no municipal rule may be relied on as a justification for violating international law. In other words: “The tail cannot wag the dog!”

Apart from the foregoing principles regarding the sanctity of treaties and the harmony that must exist between such agreements and domestic law, Greenidge said Guyana, now more than ever, should not be seen as inconsistent in its treatment of laws. “Respect for the sanctity of treaties must be done across the board, and not when it conveniently suits our needs,” Greenidge related to OilNOW.

The former Foreign Affairs Minister concluded that this entire matter can be resolved by either approaching the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) for an Advisory Opinion or utilizing a less time consuming and costly mechanism which entails CARICOM Heads triggering the Good Offices Dispute Settlement Mechanism, to establish a Working Group of Heads of Government to consider the matter.

He concluded that either of these could spare Guyanese “the poison” that has now entered the Local Content debate.