The Environmental Permit issued to ExxonMobil Guyana on June 1, 2017 by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the Liza Phase 1 Development allows for flaring under certain conditions and outlines measures that should be compiled with when such flaring becomes necessary.

The Permit states that efforts must be made to ensure all reasonable attempts are made to implement appropriate methods for controlling and reducing fugitive emissions in the design, operation, and maintenance of offshore facilities and to maximize energy efficiency and design facilities for lowest energy use. It states that the overall objective is to reduce air emissions and cost-effective and technically feasible options for doing so should be evaluated and adopted.

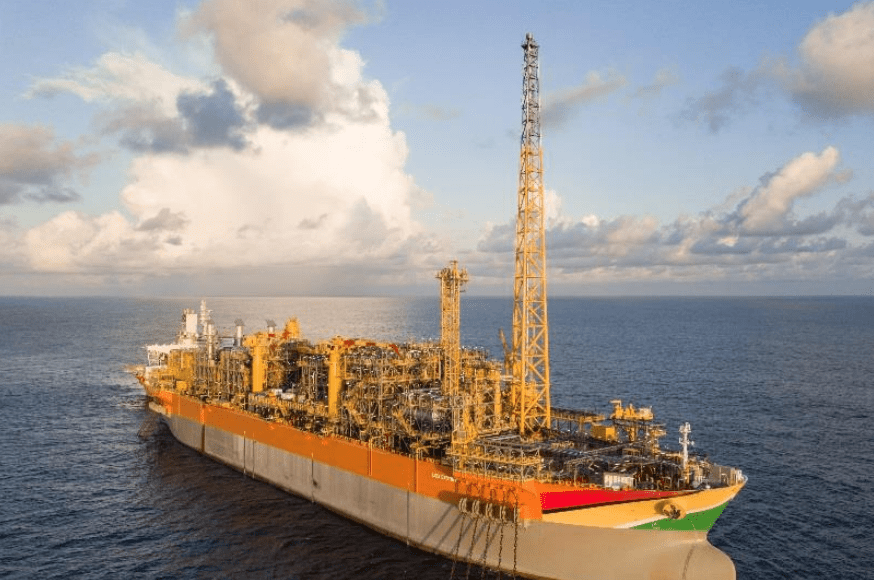

The Liza Destiny Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) vessel producing oil at the Stabroek Block offshore Guyana was designed to ensure there is no routine flaring in its daily operations. This involves the implementation of measures to manage emissions to the atmosphere and includes re-injecting produced gas which is not utilized as fuel gas on the FPSO to avoid routine flaring.

While the Permit states categorically that “routine flaring and venting are prohibited” it also outlines the circumstances that are not considered to be “routine” under which flaring is permitted.

“Routine Flaring and Venting are prohibited on the FPSO (excludes tank flashing emission, standing/working/breathing losses). Routine flaring does not include flaring related to FPSO startup, emergencies/process upsets or maintenance events,” the Permit states at page 6, under Air Quality Management.

On January 27, vibrations in the flash gas compressor on the Liza Destiny FPSO resulted in a disruption to the gas reinjection process that is used in the oil production operations, thereby reducing the volume of associated gas being reinjected into the reservoir.

In this regard, the Environmental Permit clearly outlines the procedure for handling “process upsets and loss-of-containment events” on the FPSO, which could impact the environment.

“Notify the Agency within 24 hours after process upset events or unplanned maintenance occur which result in a flaring event on the FPSO sustaining a volume of at least 10 MMSCFD and lasting 5 days or longer. Volumes from minor flaring events not requiring notification will be captured in aggregate in annual emissions reporting,” the Permit states.

It further adds that measures should be adopted “as far as practicable in keeping with the Global Gas Flaring and Venting Reduction Partnership when considering venting and flaring options under emergency or upset conditions.”

The document then outlines 29 conditions that “should be complied with for when flaring from the FPSO is necessary, particularly under emergency and/ or upset conditions.” These conditions relate to ensuring maximum safety is applied in the flaring process and that the volumes of hydrocarbons being flared are recorded and submitted to the EPA.

“Gas flaring happens with associated gas….so, it’s a by-product of the oil business and if it’s not controlled in some way through either using the gas for effective things like power plants or for fertilisers or for other things…then what happens is that it can be vented into the air which means released into the air or it can be burned when it’s released into the air, and that’s flaring,” Morgan D. Bazilian, Director of the Payne Institute and a Professor of Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines had told Guyanese reporters in an informational session last year.

He had further stated that the offshore oil operations in Guyana are engineered to be at zero routine flaring over the course of their life, adding that the country does not show up in the top 30 territories for flaring.