(The Washington Post) The stench of gasoline burned through Verónica Barboza’s nose as she stood by the edge of Lake Maracaibo, one of the largest lakes in South America, on a recent afternoon.

The soles of her shoes, she said, were stained black by the petroleum gushing from pipes under the water. Once a symbol of Venezuela’s oil richness, the lake is now contaminated by crumbling machinery spitting crude oil and bright-green blooms of algae — pollution that can be seen from space.

Swirls of green, black and beige across one of the world’s most ancient lakes were captured in September by NASA’s Earth Observatory. The satellite photos released Tuesday by the agency, experts say, underscore how Venezuela’s crisis has seeped into the environment — devastating wildlife and fishing communities as the country’s oil industry spirals into disrepair.

“The country’s situation and the environmental crisis are two sides of the same coin, and it’s stripping us from our natural wonders,” said Barboza, a 19-year-old activist at Fridays For Future Venezuela, a group of young Venezuelans advocating for environmental justice.

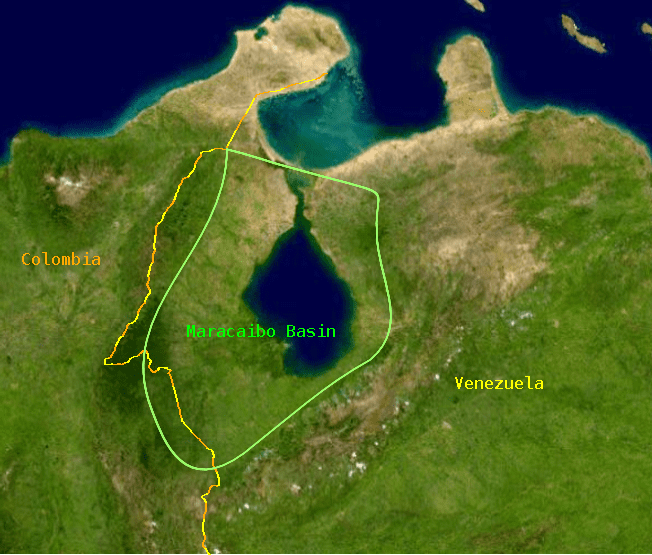

Lake Maracaibo, spanning some 5,100 square miles in northwestern Venezuela, is an estuarine lake — meaning the fresh water it was filled with thousands of years ago converges with the Caribbean’s salty seawater. The basin where it sits holds one of the largest known petroleum and gas reserves in the world, which have been extracted since the World War I era.

Pollution is not new in the place that NASA deemed “Earth’s lightning capital” for its impressive display of thunderstorms.

With more than 10,000 oil-related installations and a network of close to 16,000 miles of underwater pipelines in operation, slicks have been a constant occurrence at Lake Maracaibo. But never at the rate seen these days, said Eduardo Klein, director of the remote-sensing laboratory at Simón Bolívar University, where he uses NASA satellite images to document the oil slicks.

An oil spill is considered a crime under Venezuelan environmental law. Between 2010 and 2016, the state oil giant PDVSA was responsible for more than 46,000 spills of crude and other pollutants, according to a study by Provea, a Caracas-based human rights group. PDVSA stopped releasing data in 2016, reporting 8,250 oil spills that year — quadruple the number seen in 1999, the year that Hugo Chávez was sworn in as president.

The lack of government data has led researchers, activists and universities to try to fill the void, conducting their own studies on how many spills are taking place. According to a report from the Venezuelan Observatory of Political Ecology (OEP), a nongovernmental environmental organization, at least 53 have been detected this year to Sept. 16 across Zulia, Falcón and Anzoátegui — the three states harboring the country’s main refineries.

But recording the amount of oil is sometimes tricky — especially “when it’s not a singular spill, but you have ruptured pipelines pouring out petroleum continuously and almost every day,” Klein said.

In recent years, a lack of maintenance, a brain drain of technicians and corruption have crippled oil production, making oil accidents more common. Within the lake, thousands of wells are broken beyond repair, allowing raw crude and natural gas to bubble to the surface.

The country’s oil industry is producing and exporting close to 700,000 barrels per day, according to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which cites the reported government figures. This is equivalent to 20 percent of what PDVSA produced in 1999.

Venezuela’s Ministry of Ecosocialism, PDVSA and Omar Prieto, the state of Zulia’s governor, did not respond to requests for comment from The Washington Post.

Josué Lorca Vega, the country’s Minister of Ecosocialism, told local reporters in June that the government agency was working on acquiring oil containment and absorption systems for Venezuela’s coastal areas — adding that “oil spills are nothing out of the ordinary because historically they have always existed.”

For local fishermen, the contamination means coming back to shore with a smaller catch, foul fish and damaged equipment. Some return empty-handed and soaked in crude.

Residents told OEP that they suffer from skin rashes, that the fish tastes like gasoline, and they can no longer use the lake for family recreation.

Despite the oil-slicked water, Proyecto Sotalia, a research group that studies marine mammals in Lake Maracaibo, has recorded sightings of manatees and pink river dolphins, two endangered species, in recent expeditions. Some 145 species of fish inhabit the lake’s waters, where blue crabs and shrimp also dwell.

“Lake Maracaibo is a resilient ecosystem, and it has some mechanisms to maintain itself,” said Barboza, the environmental activist. “It’s an open system with entry into the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Venezuela, so the water is not just stuck there.”

Still, experts worry that may not be enough to protect wildlife contending with two ecological challenges: a steady flow of petroleum and oxygen-depleting algae.

The latter is a natural occurrence in the lake, said Frank Muller-Karger, a biological oceanography and remote sensing professor at University of South Florida. An extensive bloom was recorded by NASA in 2004.

The overload of nutrients pouring from both land and sea — compounded by runoff from nearby farmlands and sewage — feed activity from microorganisms such as phytoplankton and duckweed, producing the vibrant green layer captured in NASA’s satellite photos. When these creatures die, they sink to the bottom and decay — a process that causes hypoxia, or low-oxygen water.

“It’s gotten much worse, and it’s also an indication of pollution because some of it is caused by the agricultural industry’s fertilizer,” Muller-Karger said. “The bottom of the lake probably is already hypoxic almost permanently. That means organisms like fish, crabs, mollusks can’t live there, and it impacts the local fisheries and environment.”

Adding the oxygen-stifling algae into the mix, Klein said, further burdens an ecosystem grappling with a steady stream of oil pumping into its waters.

“There’s a cumulative process of pollution,” he said. “It’s not just that direct impact of animals soaked in petroleum that is associated with oil spills. It’s the years of organisms having to live in these conditions, of them maybe not tolerating it more and eventually dying off. It could wreak havoc on such an important and diverse ecosystem.”

For Barboza, who was born and raised in Maracaibo, the lake’s environmental problems feel personal. Once Venezuela’s petroleum capital, her city now stands as a grim sign of the country’s reverse in fortune. The water it borders is deemed by locals as a “soup of bolts,” a visual metaphor of the crisis.

“Nature was one of the few things that felt untouched by the chaos,” she said. “Now the crisis is snatching away a beauty that belongs to all of us and that has been a source of pride for Venezuelans. We’re so lucky to have this natural wonder, but this shows we also have the responsibility of protecting it.”